Introduction

This coming fall—November 18, 2014—will mark ten years since the Supreme Court of Canada released two seminal decisions on the Crown’s duty to consult Aboriginal peoples: Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 SCC 73 and Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director), 2004 SCC 74. This was a turning point in one of the most significant developments in the law in recent years as it applies to Canadian provincial and federal energy regulators (“Energy Regulators”)—and arguably among the most significant developments in Canadian law generally in recent years—namely, the emergence and ongoing clarification of the Crown’s duty to consult and, if necessary, accommodate Aboriginal peoples.

Ten years ago, issues surrounding Aboriginal rights and title and the Crown’s duty to consult Aboriginal peoples inhabited only the periphery of energy/regulatory law and practice. Today, for many Energy Regulators, project proponents, Aboriginal groups and intervenors, these issues have become a critical focus in the regulatory approval processes for major (and not-so-major) projects. As the Supreme Court of Canada aptly noted in a more recent decision:

“In the intervening years [since Haida], government–Aboriginal consultation has become an important part of the resource development process…”2

Given the importance of Energy Regulators in the resource development process, issues of the Crown’s duty to consult Aboriginal peoples have also become an important part of the regulatory process. However, the role and function of Energy Regulators in Aboriginal consultation and the review of Aboriginal consultation carried out by others—and how these issues fit as a part of the regulatory process—has often remained poorly understood. Regulators have struggled to define their role and understand their jurisdiction in respect of the complicated legal, historical and social issues raised by such issues.

The meeting of Aboriginal law (and its practitioners) and energy/regulatory law (and its practitioners) has not always been smooth. In the hearing rooms of today’s Energy Regulators, it is not uncommon to see Aboriginal law practitioners/legal counsel (who are well-versed in the law of Aboriginal rights and title and the Crown’s duty to consult) citing reams of Aboriginal case law to an (often somewhat confused) Energy Regulator, while often giving scant treatment to issues regarding the proper role and function of that Energy Regulator. Similarly, it is not uncommon to see Energy Regulators struggle with such submissions and attempting to reconcile such submissions with their legislative role and function—and not finding significant guidance in their legislative job descriptions.

Objective and Outline

This article will suggest that much of the confusion that has plagued this area of the law is a result of failing to properly distinguish between (i) the various legal contexts in which the duty to consult can arise; (ii) the various types of decision-making structures in which Energy Regulators operate; and (iii) the different types of parties (private or Crown agents) that can be applicants or parties before Energy Regulators. What is required is not a search for universal answers that will fit all Energy Regulators and all circumstances. Instead, what is required is an analytical framework that will assist in clarifying the nature of the consultation obligations and the role of the Energy Regulator in the context of a specific legislative framework, application and applicant.

In an effort to begin discussion of such an analytical framework, this article will suggest:

- There are three distinct legal contexts in Canada that need to be understood—(i) historic treaties; (ii) modern treaties or comprehensive land claims; and (iii) non-treaty areas.

- The Crown’s duty to consult can arise in all three contexts, but purpose, scope and extent of the duty to consult may be different in each context. Some Energy Regulators may encounter more than one such context (sometimes in the scope of a single project application) and must be alert to the potential differences in the ways the duty to consult may apply.

- The duty on an Energy Regulator to consider consultation and the scope of that inquiry depends on the mandate conferred by the legislation that creates the tribunal. The legislature may delegate either, both or neither of the powers to carry out the Crown’s duty to consult and/or determine whether adequate consultation has taken place, as a condition of its statutory decision-making process.

- The precise role of the Energy Regulator may be different depending on the nature of the application before it, the nature of the decision-making structure in place for such applications, and the Applicant before it—particularly whether the Applicant is a private company or a Crown agent.

This article is an attempt to provide a view from the vantage point of the intersection of Aboriginal and regulatory law. Those with an expertise in Aboriginal law may find its treatment of the rich and varied principle and case law of this complex discipline to be somewhat elementary. Those with an expertise in regulatory law may make the same complaint about its treatment of regulatory law and principles. This is perhaps a consequence of attempting to speak to two rather diverse audiences at once. As with so much of Aboriginal law (and with this part of the history of Canada), the dialogue is necessarily a “cross-cultural” discussion, and certain subtleties and nuances are (at least initially) apt to be sacrificed along the way.

More specifically, the objective of this article is to situate and examine the role of the Energy Regulatory in respect of the Crown’s duty to consult. Given the number and diversity of Energy Regulators on the Canadian landscape, this article does not attempt or purport to canvass each and every Energy Regulator and/or consider its legislation. Instead, it sets the more modest objective of attempting to identify and clarify the guiding principles and an analytical framework that apply in defining the role of the Energy Regulator. It is my hope that this effort may be of some use to Canadian Energy Regulators and the myriad parties that appear before them, including project proponents, Aboriginal groups and other intervenors interested in the important (but often misunderstood) role of Canadian Energy Regulators.

This article has organized in the following three parts:

- Part I provides a primer on Aboriginal rights and title and outlines three distinct legal contexts that exist in contemporary Canada — historic treaties, modern treaties and non-treaty areas;

- Part II provides a discussion of the sources, purpose and principles applicable to the Crown’s duty to consult Aboriginal peoples and an examination of how the duty applies in each of the three legal contexts identified above;

- Part III provides the primary focus of this article in discussing the role of the Energy Regulator in respect of the Crown’s duty to consult;

The overview of Aboriginal rights and title (Part I) and the Crown’s duty to consult (Part II) provides a foundation for understanding and appreciating the interrelationship between Aboriginal law principles and regulatory/administrative law applicable to Energy Regulators (Part III).

Part I: A Primer on Aboriginal Rights and Title in Canada

Section 35(1) of The Constitution Act, 19823 states:

“The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

Behind this simple phrase lies a wealth of diversity and complexity.

In Canada, there are in excess of 600 First Nations, plus numerous Inuit and Métis groups and organizations. These groups comprise numerous, rich and varied linguistic and cultural traditions. Amongst these groups, there is a broad diversity of historical and contemporary circumstances and an equally diverse range of outlook, orientation and approach. Any attempt to categorize such diversity into an artificially small number of legal frameworks risks being accused of being nothing more than generalization on a vast scale. The attempt at creating such a categorization of these legal frameworks is not meant to be disrespectful of the diversity that exists among and between Aboriginal groups but is simply an effort to make such diversity manageable for the non-specialist in Aboriginal affairs and history.

With the above caveat in mind, I suggest that there are, broadly speaking, three legal frameworks applicable to Aboriginal peoples in Canada:

- (a) the historic treaties;

- (b) the modern treaties/comprehensive land claims; and

- (c) the non-treaty context.

Each is discussed further below.

Historic Treaties in the Area that is now Canada

In some parts of Canada, it is becoming increasingly common to hear the phrase: “We are all treaty people.” It is true that treaties between the Crown and Aboriginal peoples exist in many parts of Canada covering the majority of the Canadian land mass. However, in some significant parts of Canada, treaty making remains unfinished business. It is unfortunately not uncommon for non-Aboriginal Canadians to live many years or even their entire lives in a region of Canada not knowing or understanding the treaty arrangements that may have proceeded or accompanied non-Aboriginal settlement in that area.

A comprehensive examination of these treaties (and the rules of interpretation that apply to them) is beyond the scope of this article, but the existing historic treaties can generally be grouped into the following categories:

-

Treaties of Peace and Neutrality (1701-1760)

These treaties were the product of the British and French seeking military alliances with First Nations in the context of the struggle for the control of North America. For example, the Treaty of Swegatchy and the Huron-British Treaty—both concluded in 1760 at the end of the Seven Years’ War—addressed, inter alia, issues such as the protection of First Nation village sites, the right to trade with the British and the protection of traditional practices.

-

Peace and Friendship Treaties (1725-1779)

These treaties were concluded between the British authorities in Nova Scotia and the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples of the Maritimes.

-

Upper Canada Land Surrenders and the Williams Treaties (1781-1862/1923)

These treaties focused on land cessions in the Great Lakes region. For the most part, these treaties involved one-time cash payments with ongoing obligations. In 1923, the Williams Treaties focused on land cessions (again for a fixed one-time cash payment) in the region between Georgian Bay, the Ottawa River, Lake Simcoe and the lands west of the Bay of Quinte.

-

Robinson Treaties (1850) and Douglas Treaties (1850-1854)

The Robinson treaties of 1850 were concluded between William Robinson and the primarily Ojibwa inhabitants of the northern Great Lakes region. The Robinson-Superior Treaty covered the area of the north shore of Lake Superior. The Robinson-Huron Treaty covered the Lake Huron and Georgian Bay areas. These treaties—in contrast to treaties negotiated earlier—contemplated the creation of reserves, annuities and the continued right to hunt and fish.

The Douglas Treaties—14 in all—were concluded from 1850 to 1854 between James Douglas (Chief Factor of the Hudson Bay Company and later governor of the colony on Vancouver Island) and certain First Nations on Vancouver Island. These treaties contemplated the surrender of lands near Hudson Bay Company posts on Vancouver Island in exchange for reserves, payments and the continued right to hunt and fish.

This new approach (recognizing continued rights to hunt and fish) would be further developed in the Numbered Treaties (discussed below).

-

The Numbered Treaties (1871-1921)

Between 1871 and 1921, Canada undertook 11 “numbered” treaties (i.e. Treaty No. 1, Treaty No. 2, etc.) that covered the Prairies, northern Ontario and the Peace River and Mackenzie River valleys. These treaties contemplated the surrender of lands in exchange for reserves, payments and the continued right to hunt and fish.4

The other commonly employed catagorization for these historic treaties is to consider them in the groupings of: (i) Pre-Confederation; and (ii) Post-Confederation treaties—with the dividing line drawn at 1867. The scope and content of the historic treaties remains subject to considerable debate and uncertainty. For example, the “trade clause” in a Peace and Friendship treaty of 1760/61 was the famously the subject of 1999 litigation before the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Marshall.5 A rich and detailed jurisprudence has developed regarding the interpretation of these important historic treaties.6

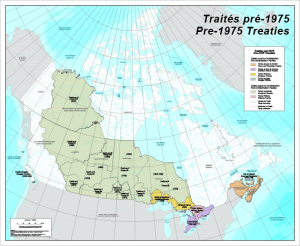

The following map7 shows the approximate location and boundaries of historical treaties in Canada.

As can be seen from the map, when the historic treaty making process concluded in the early 1900s, large sections of current-day Canada were not covered by treaties—notably the majority of British Columbia, Quebec, Newfoundland, Labrador, the Yukon, and eastern portions of the Northwest Territories and what is now Nunavut.8

As discussed below, some of these non-treaty areas were subsequently the subject of modern treaty negotiations. In addition, in some areas where the historic treaties were never fully implemented (notably, for example, in relation to Treaty No. 11 and some of the northern areas of Treaty No. 8), the Crown and the relevant Aboriginal groups have also entered into modern treaty negotiations and in some cases concluded modern agreements.

Modern Treaty Making in Canada

The modern treaty process deals with unfinished treaty making in areas of Canada where historic treaties were not concluded. Section 35(3) of The Constitution Act, 1982, clarifies:

“For greater certainty … ‘treaty rights’ includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.”

There is no bright line separation between the “historic” and the “modern” treaties. The artificial distinction is employed here simply as a matter of convenience. In most attempts at categorization, the first so-called modern day treaty is considered to be the “James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement”, signed in 1975. Perhaps the primary distinguishing feature of the modern treaties is their length and detail—typically consisting of hundreds of pages with numerous detail appendices and maps—compared to the historic treaties.

Mr. Justice Binnie, of the Supreme Court of Canada has observed:

“The increased detail and sophistication of modern treaties represents a quantum leap beyond the pre-Confederation historical treaties … and post-Confederation treaties such as Treaty No. 8 (1899) … The historical treaties were typically expressed in lofty terms of high generality and were often ambiguous. The courts were obliged to resort to general principles (such as the honour of the Crown) to fill the gaps and achieve a fair outcome. Modern comprehensive land claim agreements, on the other hand, starting perhaps with the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement (1975), while still to be interpreted and applied in a manner that upholds the honour of the Crown, were nevertheless intended to create some precision around property and governance rights and obligations. Instead of ad hoc remedies to smooth the way to reconciliation, the modern treaties are designed to place Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations in the mainstream legal system with its advantages of continuity, transparency, and predictability.”9

Modern Treaty-Making North of 60

The modern treaty making process has, to date, been far more prolific in Northern Canada. Since 1973, 16 comprehensive land claims have been reached in the northern territories (Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut).

- In the Yukon, there are 14 resident First Nations. To date, land claims agreements with 11 of those First Nations have been concluded and implemented. These 11 are, with the dates their agreements were implemented: the Champagne and Aishihik First Nation (1993); the Teslin Tlingit Council (1993); the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation (1993); the First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun (1993); the Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation (1997); the Selkirk First Nation (1997); the Tr’ondek Hwech’in First Nation (1998); the Ta’an Kwach’an First Nation (2002); the Kluane First Nation (2003); the Kwanlin Dun First Nation (2005); and the Carcross Tagish First Nation (2005).10

- In the Northwest Territories, to date land claims agreements with the following Aboriginal groups have been concluded and implemented: Inuvialuit (1984), Gwich’in (1992), Sahtu Dene and Métis (1994), and Tli’cho (2005). In the southern part of the Northwest Territories, land claim negotiations continue with a number of First Nations and Métis groups.

- In Nunavut, the Nunavut Final Agreement concluded in 1993 led to the division of the (formerly larger) Northwest Territories and the creation of the new territory of Nunavut in 1999.

Modern day treaties in Canada generally have two aspects: (i) comprehensive land claim settlements; and (ii) self-government agreements. Some agreements address both lands claims and self-government. However, some agreements address only land claims issues, but leave self-government negotiations to be concluded separately. For example, in the Northwest Territories, the Tli’cho Final Agreement (2005) addresses both land claims and self-government; however, the earlier agreements in the territory (Inuvialuit, Gwich’in and Sahtu) addressed only comprehensive land claims and left self-government to subsequent (and ongoing) negotiations.

Modern Treaty-Making South of 60

In the rest of Canada (south of the 60th parallel) during this same time period, a relatively small number of other comprehensive land claims and self-government arrangement have been concluded:

- In Quebec, there was the aforementioned James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1977) and the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (1978).

- The offshore island and marine areas adjacent to Quebec were the subject of the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement (2008) and the Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement (2012).

- Northern Labrador was the subject of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (2005).

- In British Columbia, there has been the Nisga’a Final Agreement (2000), the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement (2009) and Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement (2011). There have also been self-government arrangements with the Sechelt Indian Band11 (1986) and Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement (2005).

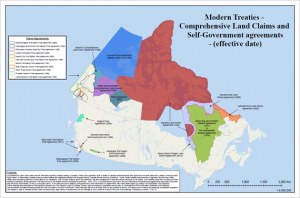

The following map shows the locations of Modern Treaties, including both Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government agreements.12

The BC Treaty Commission Process

British Columbia is where there is perhaps the largest concentration of unfinished treaty business in Canada. As discussed above, there are no historic or modern treaties coving the majority of British Columbia. However, the governments of Canada and British Columbia have been engaged in treaty negotiations with numerous First Nations pursuant to the B.C. Treaty Commission Process. The Treaty Commission and the treaty process were established in 1992 by agreement among Canada, B.C. and the First Nations Summit.

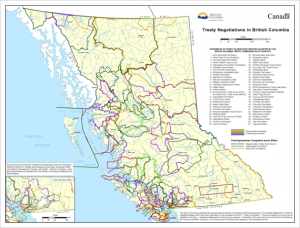

The following map shows the numerous (overlapping) claims submitted to the B.C. Treaty Commission process:13

Some Indian Bands in British Columbia are negotiating individually, while other Bands have combined to form larger treaty negotiation groups. Of the more than 200 Indian Bands in British Columbia there are slightly more than 100 that are participating in the B.C. Treaty Commission process—grouped into about 60 treaty negotiations tables.14 Of these 60 treaty negotiation groups:

- 2 (Maa-nulth and Tsawwassen) are implementing treaty agreements;

- 3 have completed final agreements that are not yet implemented;

- 5 are in final agreement negotiations or completed agreements in principle;

- 10 are in “advanced” agreement-in-principle negotiations;

- 20 are in “active” agreement-in-principle negotiations; and

- 20 are described as “not currently negotiating a treaty.”

Many observers have expressed frustration at the relatively slow pace of treaty negotiations and the fact that—following over 20 years of the BC Treaty Commission process—there are no more than a handful of final agreements. However, when one considers that the current situation was created over the course of a few hundred years, it is perhaps unrealistic to hope or expect that treaty negotiations will be concluded quickly. In the past several years, a number of First Nations in BC have signed “incremental” agreements that provide the First Nation with access or title to a limited number of parcels of Crown land in advance of a full treaty agreement.

Modern Land Claims – Common Features

Given that the modern treaty making process in Canada already spans a four decade history, it is not surprising that there is considerable variation in the approach and details of the above mentioned modern treaties. Again at the risk of generalization, the following discussion will focus on the common elements. A common approach in these agreements, which each contain their own structural and procedural arrangements, is as follows:

- a specific tract of land is identified and confirmed as land held by the Aboriginal group in fee simple;

- a larger tract of land is identified as a management area, within which the Aboriginal group, federal government and either territorial or provincial government participate in land use planning and land use permitting and approvals; and

- a larger area within which certain land use rights, such as hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering, continue to apply. This larger area often overlaps with management areas or other areas within which neighbouring Aboriginal groups have and exercise rights.

Clearly, decisions regarding land and resource projects on the fee simple lands under these agreements are within the control of the Aboriginal group, subject to the laws and regulations of the Aboriginal group, as well as to any generally applicable environmental assessment or environmental protection laws and regulations. The more difficult and nuanced an issue is the more difficult it is to identify the degree of control exercised by the Aboriginal group on the second and third categories of land identified above. This will be discussed further below in Part II.

Non-Treaty Areas in Canada

Notwithstanding the historic and modern treaty making efforts, there remain significant portions of Canada where treaties have never been signed. For example, in British Columbia, where there are over 200 First Nations (of slightly more than 600 in all of Canada), the vast majority of Aboriginal groups do not have a treaty in place.15 In the absence of treaties, the major developments came from judicial decisions regarding Aboriginal rights and title. In the hierarchical world of the courts, there are no judicial pronouncements more important than those that come from the Supreme Court of Canada and so the following overview will focus on the major milestones from that Court and constitutional developments.

The Calder Decision

In the late 1960’s, Frank Calder, the Nishga Tribal Council and four Indian bands, brought an action against the Attorney-General of British Columbia for a declaration “that the aboriginal title, otherwise known as the Indian title, of the Plaintiffs to their ancient tribal territory… has never been lawfully extinguished”. The claim was based in part on The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763. The action was dismissed at trial and the Court of Appeal rejected the appeal.

- A seven judge panel of the Supreme Court of Canada heard the appeal and, in a procedurally unusual decision, split 3-3-1.16

- Three judges (Hall, Spence and Laskin JJ.,) would have allowed the appeal, and rejected as “wholly wrong” the proposition that “after conquest or discovery the native peoples have no rights at all except those subsequently granted or recognized by the conqueror or discoverer.” They found that Aboriginal title continued and it had not been surrendered.

- Three judges (Martland, Judson and Ritchie JJ) voted to dismiss the appeal based on the very terms of the Proclamation and “upon the history of the discovery, settlement and establishment of what is now British Columbia.” Since the area in question did not come under British sovereignty until 1846, the Appellants were not any of the several nations or tribes of Indians who lived under British protection in 1763 and they were outside the scope of the Proclamation.

- The seventh judge (Pigeon J.) refused to decide the substantive issue, instead concluding that the Court had no jurisdiction (in the absence of a fiat of the Lieutenant-Governor of that Province) to make the declaration prayed for, being a claim of title against the Crown in the right of the province of British Columbia.

Given the unusual 3-3-1 split, the resulting decision was inconclusive, but this decision is generally credited with restarting the modern treaty making process in Canada. (The Nisga’a Final Agreement became effective in 2000.)

Section 35 Jurisprudence

Following the introduction of s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Supreme Court of Canada addressed its scope in R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 SCR 1075 [Sparrow]. The Court held that section 35(1) needs to be construed in “a purposive way” and that a generous, liberal interpretation is demanded given that the provision is to affirm Aboriginal rights. Legislation that affects the exercise of aboriginal rights will be valid if it meets the test for justifying an interference with a right recognized and affirmed under s. 35(1).

Following the Sparrow decision in 1990, an increasing volume of Aboriginal law litigation throughout the 1990s focused on Aboriginal rights and title—including the content of such rights and how they could be established. These issues made their way to the Supreme Court of Canada in the late 1990s in a series of appeals. Arguably, two of the most important from this time were:

-

R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507.

This appeal, heard along with the companion appeals in R. v. N.T.C. Smokehouse Ltd., [1996] 2 S.C.R. 672, and R. v. Gladstone, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 723, addressed the issue left unresolved by the Supreme Court of Canada in its judgment in R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075, namely: How are the aboriginal rights recognized and affirmed by s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 to be defined? To be an aboriginal right an activity must be an element of a practice, custom or tradition integral to the distinctive culture of the aboriginal group claiming the right. The practices, customs and traditions which constitute aboriginal rights are those which have continuity with the practices, customs and traditions that existed prior to contact with European society.

-

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010 [Delgamuukw].

This appeal addressed the content of Aboriginal title, how it is protected by s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 and the requirements necessary to prove it. The Court held that Aboriginal title encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land held pursuant to that title for a variety of purposes, which need not be aspects of those aboriginal practices, customs and traditions which are integral to distinctive aboriginal cultures. In order to establish a claim to aboriginal title, the aboriginal group asserting the claim must establish that it occupied the lands in question at the time at which the Crown asserted sovereignty over the land subject to the title.

However, the Court did not identify precisely where Aboriginal rights or title existed or precisely define their content. This was left to be defined through either further litigation or settled by treaty negotiations. As discussed above, a number of the Aboriginal groups in the province are currently involved in treaty negotiations with the Crown—while other Aboriginal groups are seeking to establish Aboriginal title and/or rights through the courts. In the meantime, the precise location of Aboriginal title in British Columbia and other such areas remains undefined. In the absence of such definition, these Aboriginal groups have asserted Aboriginal rights and title over large tracts of Crown land. Many of these asserted “traditional territories” overlap with neighbouring claims.

Both the further definition of Aboriginal rights and Aboriginal title remain a work in progress:

- In respect of Aboriginal rights, the Supreme Court of Canada has considered a number of specific claims to specific rights. For example, the Court has recently addressed a number of claims to commercial fishing rights.17

- In respect of Aboriginal title, the Supreme Court of Canada has had the occasion to elaborate on the issue18, and it currently has a very significant case under reserve that will likely provide an opportunity to further clarify the nature of Aboriginal title.19

- The Supreme Court of Canada has also issued a series of decisions on Metis rights.20

The key message from Part I is that, in order to begin correctly, it is necessary that all participants (Energy Regulators and parties appearing before them) appreciate and understand the applicable legal context of the Aboriginal groups that may participate in regulatory processes. Energy Regulators, whose jurisdiction is confined by provincial, territorial or federal boundaries, may encounter Aboriginal groups in all three legal contexts. Some groups may have treaty rights (based on historic and/or modern agreements) while others many have asserted or established Aboriginal rights. Understanding the context can help to avoid errors that may arise in applying case law, principles or practices that have been developed or discussed in a different legal context. The proper understanding of the legal context of Aboriginal and treaty rights is important in considering the Crown’s duty to consult, which is canvassed in Part II.

Part II: The Duty to Consult21

The Duty to Consult – Origins and Overview of the Case Law

One of the first observations about the duty to consult is that it is in its origins (and still remains) primarily judge-made law. Unlike many of the issues faced by Energy Regulators (which are grounded in statute, regulations or government policy), the law regarding the Crown’s duty to consult is primarily the result of jurisprudence. While consultation policies and (recently) legislation have begun to play a larger role, it is still the jurisprudence that plays the dominant chords.

The duty to consult first received significant judicial attention in the non-treaty areas of Canada—particularly in British Columbia. There were references to Crown consultation in the context of the discussion of Aboriginal rights22 and Aboriginal title,23 but the scope and extent of any legal duty remained indeterminate. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, debate raged in the lower courts regarding when, if ever, the Crown had a “duty to consult” in circumstances where Aboriginal rights and title were asserted, but unproven.

This issue was addressed by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004 when it issued two seminal decisions on the Crown’s duty to consult: Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 2004 SCC 73 and Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director), 2004 SCC 74. These two cases arose in areas of British Columbia where treaties were never signed historically between the Crown (the federal and/or provincial governments) and First Nations.

From the very beginning, it was clear to the Supreme Court of Canada (and many observers) that the understanding of the duty to consult had only begun. In Haida, the Court stated:

“This case is the first of its kind to reach this Court. Our task is the modest one of establishing a general framework for the duty to consult and accommodate, where indicated, before Aboriginal title or rights claims have been decided. As this framework is applied, courts, in the age-old tradition of the Common Law, will be called on to fill in the details of the duty to consult and accommodate.” (para. 11)

This work of “filling in the details” of duty to consult has been underway ever since—including occasional decisions from the Supreme Court of Canada. Notable milestones include the following:

- In 2005, the Supreme Court of Canada applied this new framework of the Crown’s duty to consult in the context of a historic treaty (Treaty 8 signed in 1899). Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), 2005 SCC 69.24

- In 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada applied the framework in the context of a modern treaty (signed in 1997). Beckman v. Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation, 2010 SCC 53.25

- Also in 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada reaffirmed how the framework operates in a non-treaty context—with a particular emphasis on whether past infringements of Aboriginal rights could be a trigger for the duty to consult—and (importantly for the subject of this article) examined the place of government tribunals in consultation and the review of consultation. Rio Tinto Alcan Inc. and BC Hydro v. Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, 2010 SCC 43.

- Most recently in 2013, the Supreme Court of Canada considered the question of to whom the Crown owes a duty to consult—including whether individuals can assert a duty to consult or invoke treaty rights—and the proper procedure for raising allegations of inadequate consultation. Behn v Moulton Contracting Ltd, 2013 SCC 26.

The following discussion will review the major aspects of this case law—focusing on those issues of key interest to Energy Regulators.

The Framework for the Duty to Consult in Non-Treaty Areas – Haida

In Haida, the Court held that the government has a duty to consult with Aboriginal peoples that is grounded in the principle of the “honour of the Crown.” Pending settlement of Aboriginal claims, the Supreme Court of Canada determined that the Crown’s duty “arises when the Crown has knowledge, real or constructive of the potential existence of the Aboriginal right or title and contemplates conduct that might adversely affect it.”26

The scope and content of the duty to consult and accommodate varies with the circumstances. In general terms, the scope of the duty is proportionate to a preliminary assessment of two variables: the strength of the case supporting the existence of the right or title, and the seriousness of the potentially adverse effect upon the right or title claimed.27 This produces a “spectrum” of consultation. In cases where the claim to title is weak, the Aboriginal right limited, or the potential for infringement minor, the only duty may be to give notice, disclose information and discuss any issues raised in response to the notice.28 At the other end of the spectrum, where a strong prima facie case for the claim is established, the right and potential infringement is of high significance to the Aboriginal peoples, and the risk of non-compensable damage is high, “deep consultation”, aimed at finding a satisfactory interim solution, may be required.29 While the precise requirements will vary with the circumstances, the consultation required in these cases may entail the opportunity to make submissions for consideration, formal participation in the decision-making process, and provision of written reasons to show that Aboriginal concerns were considered and to reveal the impact they had on the decision. This list is neither exhaustive nor mandatory in every case. Other cases fall between these two extremes. Each case must be approached individually. Each case must also be approached flexibly, since the level of consultation required may change as the process goes on and new information comes to light. The Supreme Court of Canada has directed that the “controlling question” in all situations is “what is required to maintain the honour of the Crown and to effect reconciliation between the Crown and the Aboriginal peoples with respect to the interests at stake.”30

The effect of good faith consultation may be to reveal a “duty to accommodate”. Where a strong prima facie exists for the claim, and the consequences of government’s proposed decision may affect it in a significant way, addressing the Aboriginal concerns may require “taking steps to avoid irreparable harm or to minimize the effects of infringement, pending final resolution of the underlying claim.”31

The right to be consulted about proposed activities on Crown land does not provide Aboriginal groups with a “veto.”32 There is no duty to agree.

Third parties, such as private oil and gas, mining or forestry companies, do not have a legal duty to consult. However, that does not mean they have no role to play:

“The Crown alone remains legally responsible for the consequences of its actions and interactions with third parties, that affect Aboriginal interests. The Crown may delegate procedural aspects of consultation to industry proponents seeking a particular development; this is not infrequently done in environmental assessments.” [Emphasis added.]33

The permissible scope and extent of delegation of “procedural aspects” of consultation (and how such delegation is carried out) is a source of ongoing debate. In practice, this has frequently meant that the lion’s share of the consultation obligation falls to industrial proponents.

As further discussed in Part III, this observation is especially important in the context of the role of the Energy Regulator—where the Applicant is most often an “industry proponent seeking a particular development.” The ability of the Crown to delegate “procedural aspects” of consultation to industry proponents seeking a particular development is important in the context of determining the role of Energy Regulators—who may have a role in assessing the adequacy of consultation carried out by a (private) proponent, but who may or may not have a role in assessing the adequacy of Crown consultation in respect of the same project.

The Framework Contemplates an Administrative Process

The decision at issue in Haida was not the product of an administrative tribunal (much less a quasi-judicial Energy Regulator). Nevertheless, the Court provided some commentary on how an administrative regime may be an appropriate forum for addressing the Crown’s duty to consult:

The government may wish to adopt dispute resolution procedures like mediation or administrative regimes with impartial decision-makers in complex or difficult cases.34

The Court went on to note that the choice of how to structure such a process rested with the government:

It is open to governments to set up regulatory schemes to address the procedural requirements appropriate to different problems at different stages, thereby strengthening the reconciliation process and reducing recourse to the Courts35.

While noting that “[t]o date, the Province has established no process for this purpose”, the Court nevertheless outlined what standard of review would apply to any administrative process that might be set up for such a purpose.36 The Court concluded this discussion with another reference that suggests the parallels between this area of Aboriginal law and administrative/regulatory law: “The focus…is not on the outcome, but on the process of consultation and accommodation.”37

This discussion would be picked up an elaborated in later cases (notably Carrier Sekani). However, first it is necessary to examine Haida’s companion case—Taku River—for what it can teach regarding the role of administrative processes and decision-making.

The Framework Applied to a (non-quasi-judicial) Administrative Process – Taku River

The Supreme Court’s decision in Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director), 2004 SCC 74 was released together with the Haida decision. Unlike the governmental decision at issue in Haida, the decision-making process reviewed in Taku followed a recommendation resulting from an environmental assessment process unfolding under a legislatively established administrative scheme—although not one involving a quasi-judicial regulatory tribunal hearing in the manner common to Energy Regulators. The project at issue involved reopening an old mine site and developing an access road. While the application was being considered, it became subject to the then-newly passed the Environmental Assessment Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 119.38 One of the purposes of the Environmental Assessment Act (as it read at the time), set out in former section 2(e), was “to provide for participation, in an assessment under this Act, by… First Nations…”. The Taku River Tlingit were invited and agreed to participate in the “project committee” and various sub-committees. Ultimately, the majority of the project committee members prepared a written recommendations report to refer the application for a project approval certificate to the Ministers for decision. The First Nation disagreed with the recommendations contained in the report and prepared its own report stating their concerns with the process and the proposal. The Ministers approved the proposed project and a Project Approval Certificate was issued, subject to detailed terms and conditions.

The Supreme Court of Canada found that the province was under a duty to consult with the Taku River Tlingit in making the decision to reopen the mine.39 The Court found that acceptance of the Taku River Tlingit’s title claim for negotiation under the B.C. Treaty Commission Process established a prima facie case in support of its Aboriginal rights and title and that the potential for negative impacts on the Taku River Tlingit’s claims was high.40 The Court concluded that the Taku River Tlingit were “entitled to something significantly deeper than minimal consultation under the circumstances, and to a level of responsiveness to its concerns that can be characterized as accommodation.”41

However, after reviewing the process that had unfolded through the environmental assessment, the Court concluded that the consultation provided by the province was adequate.42 Notably, the Court confirmed that the province was not required to establish a separate consultation process to address Aboriginal concerns, but that this could take place within the existing administrative process.

“The province was not required to develop special consultation measures to address TRTFN’s [Taku River Tlingit First Nation’s] concerns, outside of the process provided for by the Environmental Assessment Act, which specifically set out a scheme that required consultation with affected Aboriginal peoples.”43

In reviewing the extensive participation of the Taku River Tlingit in multiple stages of the review, the Court found that, by the time the assessment was concluded, the concerns of the First Nation were well understood and had been meaningfully discussed. Thus, the Crown “had thoroughly fulfilled its duty to consult.”44

The Court noted that further, more detailed consultations would occur through the project permitting phase, as well, allowing the Crown to continue to discharge its obligation to consult and, where necessary, accommodate Aboriginal concerns.

The Project Committee concluded that some outstanding TRTFN concerns could be more effectively considered at the permit stage or at the broader stage of treaty negotiations or land use strategy planning. … The Project Committee, and by extension the Ministers, therefore clearly addressed the issue of what accommodation of the TRTFN’s concerns was warranted at this stage of the project, and what other venues would also be appropriate for the TRTFN’s continued input. It is expected that, throughout the permitting, approval and licensing process, as well as in the development of a land use strategy, the Crown will continue to fulfill its honourable duty to consult and, if indicated, accommodate the TRTFN.”45

It is clear from the discussion in Haida and Taku that the duty consult framework included, from the very beginning, contemplation of an important role for administrative decision-making within the existing environmental and regulatory review process—even if such processes did not address all outstanding issues. Further clarification of the role of Energy Regulators would be some years in coming. However, the broad outlines of the approach that emerged were visible in the Court’s early decisions.

The Duty to Consult in Historic Treaty Areas – Mikisew

Following the establishment of the framework for the duty to consult in 2004, one of the first questions to arise was how the duty to consult applied in the context of treaty rights. In 2005, the Court considered the duty to consult in the context of a historic treaty—Treaty 8 concluded in 1899.

The case involved a challenge to Ministerial approval of a proposal to re-establish a winter road through Wood Buffalo National Park. The Mikisew Cree First Nation, a Treaty 8 signatory, objected to the proposed road on the grounds that it would infringe on their hunting and trapping rights under Treaty 8. Parks Canada had provided a standard information package about the road to the First Nation, and the First Nation was invited to informational open houses along with the general public. Parks Canada did not consult directly with the First Nation about the road, or about means of mitigating impacts of the road on treaty rights, until after important routing decisions had been made. The First Nation challenged the decision of the Minister of Canadian Heritage, the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, to authorize the construction of the road on the grounds that the Minister had not adequately consulted the First Nation about the road.

Treaty Number 8 contains the following clause (which is included in similar terms in most of the other numbered treaties)46:

“And Her Majesty the Queen HEREBY AGREES with the said Indians that they shall have right to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract surrendered as heretofore described, subject to such regulations as may from time to time be made by the Government of the country, acting under the authority of Her Majesty, and saving and excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.” [Emphasis added.]

The Court confirmed that Treaty 8 contemplated that land would be “taken up”, but found that the treaty did not specify the process by which such taking up would occur. The Court employed the duty to consult to fill this procedural gap:

Both the historical context and the inevitable tensions underlying implementation of Treaty 8 demand a process by which lands may be transferred from the one category (where the First Nations retain rights to hunt, fish and trap) to the other category (where they do not). The content of the process is dictated by the duty of the Crown to act honourably.47

The Court held that Treaty 8 confers on the Mikisew Cree substantive rights (hunting, trapping, and fishing) along with the procedural right to be consulted about infringements of the substantive rights. The Supreme Court found that, because the taking up adversely affected the First Nation’s treaty right to hunt and trap, Parks Canada was required to consult with the Mikisew Cree before making its decision.

The Court noted that a similar sliding scale of consultation obligations applied in a treaty context as in a non-treaty context. However, in place of the “strength of claim” (for an asserted but unproven right) the Court substituted the “specificity of the treaty promise”. The second variable (adverse effect) remained substantially unchanged, with the Court stating that “adverse impact is a matter of degree, as is the extent of the Crown’s duty.”

The historic treaty clearly altered how the duty to consult applied. The Court held that, while the winter road would affect Mikisew Cree treaty hunting and trapping rights, this was a fairly minor road that was built on lands “surrendered” by the Mikisew Cree when they signed Treaty 8. As a result, the lower end of the consultation spectrum was engaged. This meant Parks Canada should have provided notice to the Mikisew Cree, and should have engaged them directly to solicit their views and to attempt to minimize adverse impacts on their rights. As Parks Canada had unilaterally determined important matters like road alignment before meeting with the Mikisew Cree, the Court held that the Crown’s duty to consult had not been adequately discharged.

The Duty to Consult in Modern Treaty Areas – Little Salmon

The 2004/2005 decisions outlined how the duty to consult applied in non-treaty and historic treaty areas. In 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision in Beckman v. Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation which addressed how the Crown’s duty to consult Aboriginal groups about Crown decisions applies in the context of modern land claims agreements.

The case arose in respect of the 1997 Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation Final Agreement (the “Final Agreement”), which the Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation entered into with the Yukon and Canadian governments.48 In 2001, the government received an application for an agricultural land grant of some 65 hectares of Yukon Crown Land within the traditional territory covered by the Final Agreement. The Final Agreement provided that members of Little Salmon/Carmacks have the right to access Crown land in their traditional territory for subsistence harvesting except where the land in question is subject to an agreement for sale as was sought in the Application. The Application was reviewed in a series of administrative review processes including:

- A “pre-screening” by the Agriculture Branch and the Lands Branch as well as the Land Claims and Implementation Secretariat;

- A more in-depth technical review by the Agriculture Land Application Review Committee (“ALARC”) – a body that predated and was completely independent from the treaty. ALARC recommended that the Applicant reconfigure his parcel for reasons related to the suitability of the soil and unspecified environmental, wildlife, and trapping concerns. The Applicant complied.

- A further level of review by the Land Application Review Committee (“LARC”), a committee composed of representatives of the federal, territorial, provincial government agencies as well as First Nations including the Little Salmon/Carmacks. LARC also predated and was completely independent from the treaty.

By way of letter to LARC, Little Salmon/Carmacks expressed concerns regarding the Application. However, no representative of Little Salmon/Carmacks attended the meeting and there was no request for an adjournment. The concerns raised in the letter were considered by LARC, but LARC ultimately approved the Application. The Director of Agriculture Branch of the Yukon government (the “Director”) considered and confirmed LARC’s approval.

The Little Salmon/Carmacks sought judicial review of the Director’s decision to approve the Application. There were two major issues: 1. Was the Yukon government required to consult with and, if necessary, accommodate Little Salmon/Carmacks beyond what was expressly required by the Final Agreement? 2. If so, what scope of consultation was required and had the government’s duty been discharged?

The Supreme Court of Canada issued two judgments: one supported by seven judges, and another supported by two judges. While the two judgements are technically “concurring” opinions (as they agreed on the disposition of the particular case), they represent fundamentally different views on how the duty to consult should apply in the context of modern treaties.

The Majority Decision

Binnie J. writing for the seven-judge majority emphasised that the Final Agreement reflects “a balance of interests” and that the Yukon treaties are intended, in part, to replace expensive and time-consuming ad hoc procedures with mutually agreed upon legal mechanisms that are efficient but fair.

On the first issue (whether the duty to consult applied), the majority decision concluded that “duty to consult is derived from the honour of the Crown which applies independently of the expressed or implied intention of the parties.” The Majority stated:

…the procedural gap created by the failure to implement Chapter 12 had to be addressed, and the First Nation, in my view, was quite correct in calling in aid the duty of consultation in putting together an appropriate procedural framework.49

The majority stated: “Consultation can be shaped by agreement of the parties, but the Crown cannot contract out of its duty of honourable dealing with Aboriginal people.”50

When a modern treaty has been concluded, the first step is to look at its provisions and try to determine the parties’ respective obligations, and whether there is some form of consultation provided for in the treaty itself. If a process of consultation has been established in the treaty, the scope of the duty to consult will be shaped by its provisions.

The majority emphasized that “the honour of the Crown may not always require consultation. The parties may, in their treaty, negotiate a different mechanism which, nevertheless, in the result, upholds the honour of the Crown.”51 However, in this case, the majority concluded that the Final Agreement did not exclude the duty to consult and, if appropriate, accommodate.

On the second issue (what scope of consultation was required and whether the duty to consult had been fulfilled), the majority reviewed the negotiated definition of Consultation contained in the Final Agreement and found it to be a reasonable statement of the content of consultation “at the lower end of the spectrum.” The majority concluded that “consultation was made available and did take place through the LARC process.”52 The majority confirmed that “participation in a forum created for other purposes may nevertheless satisfy the duty to consult if in substance an appropriate level of consultation is provided.”53 On the facts, the majority concluded that the requirements of the duty to consult were met.

The First Nation had argued that the legal requirement was not only procedural consultation but “substantive accommodation.” In this case, in its view, accommodation must inevitably lead to rejection of the Application. The majority firmly rejected this argument and concluded that “nothing in the treaty itself or in the surrounding circumstances gave rise to a requirement of accommodation.”54

The Minority Decision

Deschamps J. writing for a two-judge minority agreed with the result, but her reasons for doing so were very different. The minority emphasized that the Final Agreement was the product of extensive negotiations between the parties.

To add a further duty to consult to these provisions would be to defeat the very purpose of negotiating a treaty. Such an approach would be a step backward that would undermine both the parties’ mutual undertakings and the objective of reconciliation through negotiation. This would jeopardize the negotiation processes currently under way across the country. The minority expressed the concern that “the courts must ensure that this duty is not distorted and invoked in a way that compromises rather than fostering negotiation.”

The fundamental difference between the majority and the minority was that the minority disagreed that any “procedural gap” existed in this case, and disagreed with superimposing the Common Law duty to consult on the treaty.

Deschamps J. (for the minority) agreed in principle that if there was a procedural gap in a modern treaty then the Common Law duty to consult could be applied to fill that gap. However, the minority examined the treaty’s transitional provisions and concluded that no such gap could be found in the treaty in question.55

Deschamps J. would appear to draw a distinction between the duty to consult in the context of asserted but unproven claims and the duty to consult in the context of a treaty—going so far as to state that it would be “misleading” to consider the duty to consult to be the same duty in both contexts:

Moreover, where, as in Mikisew, the Common Law duty to consult must be discharged to remedy a gap in the treaty, the duty undergoes a transformation. Where there is a treaty, the function of the Common Law duty to consult is so different from that of the duty to consult in issue in Haida Nation and Taku River that it would be misleading to consider these two duties to be one and the same. It is true that both of them are constitutional duties based on the principle of the honour of the Crown that applies to relations between the Crown and Aboriginal peoples whose constitutional — Aboriginal or treaty — rights are at stake. However, it is important to make a clear distinction between, on the one hand, the Crown’s duty to consult before taking actions or making decisions that might infringe Aboriginal rights and, on the other hand, the minimum duty to consult the Aboriginal party that necessarily applies to the Crown with regard to its exercise of rights granted to it by the Aboriginal party in a treaty.56

The minority looked to the provisions of the Final Agreement itself—in particular the assessment process provided for in the Final Agreement that applied to the Application—and concluded that there are provisions in the Final Agreement that govern the very issue of whether the Crown is required to consult the First Nation before exercising its right to transfer land.

The requirements of the processes in question included not only consultation with the First Nation concerned, but also its participation in the assessment of the project. Any such participation would involve a more extensive consultation than would be required by the Common Law duty in that regard. Therefore, nothing in this case can justify resorting to a duty other than the one provided for in the Final Agreement.

The minority concluded that the process that led to the decision on the Application was consistent with the provisions of the Final Agreement and that there was no legal basis for finding that the Crown breached its duty to consult.

Implications of the Decision

The Little Salmon/Carmacks decision, along with the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Moses57 were the Supreme Court’s first opportunities to apply jurisprudence on the Crown’s duty to consult in the context of modern treaties and land claim agreements.

For many of the existing modern land claims agreements—particularly the earlier agreements and those in the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut (discussed above)—the result of the majority decision is that there will be continued uncertainty as to whether government is under a duty, and the extent of that duty, to consult Aboriginal groups when making land and resource management decisions. While the Little Salmon/Carmacks decision indicates that governments can, through negotiation of treaties, narrow and define the extent of the duty to consult, the fact remains that, where this has not been done in existing treaties, the Common Law duty to consult will continue to apply and will continue to be a potential source of disagreement between governments and Aboriginal treaty signatories as to whether the duty is triggered and what it requires governments to do.

Some recent modern treaties such the Tsawwassen Final Agreement in British Columbia have included provisions specifying that the treaties contain an “exhaustive list of the consultation obligations of Canada and British Columbia.”58 The Little Salmon/Carmacks decision recognizes that courts should defer to the intentions of the parties where clearly expressed in the treaty and where not inconsistent with the honour of the Crown. It can be expected that future treaties will continue to address with greater specificity how the parties intend the Crown’s duty to consult will apply in those treaties.

In respect of fulfilling the duty to consult, it is notable that all nine judges of the Supreme Court of Canada was unanimous in concluding that the steps undertaken by the Government of the Yukon were adequate to fulfill the Crown’s obligation. It is clear that allowing First Nations to participate in a forum created for other purposes may nevertheless satisfy the duty to consult if in substance an appropriate level of consultation is provided. On the facts of this case—where the First Nation failed to attend the meeting, submitted its concern by letter and those concerns were considered by the decision-maker—the Court concluded that the requirements of the duty to consult were met.

Special Issues – Past Wrongs

In addition to clarifying how the duty to consult applies differently in different legal contexts (non-treaty, historic treaty and modern treaty areas), the jurisprudence as also wrestled with a number of related scoping issues. Two will be canvassed here given their importance for Energy Regulators: (i) the issue of past infringements; and (ii) the issue of to whom the duty to consult is owed.

In Rio Tinto the Court commented on the significance of past grievances or historical infringements in the context of what is required to establish the possibility that the Crown conduct may affect the Aboriginal claim or right:

“The [First Nation] must show a causal relationship between the proposed government conduct or decision and a potential for adverse impacts on pending Aboriginal claims or rights. Past wrongs, including previous breaches of the duty to consult, do not suffice. …

An underlying or continuing breach, while remediable in other ways, is not an adverse impact for the purposes of determining whether a particular government decision gives rise to a duty to consult. …

The question is whether there is a claim or right that potentially may be adversely impacted by the current government conduct or decision in question. Prior and continuing breaches, including prior failures to consult, will only trigger a duty to consult if the present decision has the potential of causing a novel adverse impact on a present claim or existing right.”59

This clarification of the law regarding the duty to consult has significantly sharpened the focus of inquiry in front of Energy Regulators. Prior to this decision, significant debate took place in regulatory hearings regarding whether the scope of the duty to consult required consultation in respect of pre-existing facilities that we, in some manner, related to the subject matter of the application in front of the Energy Regulator. Two examples can be seen in proceeding before the British Columbia Utilities Commission:

- In proceedings in respect of B.C. Transmission Corporation’s (BCUC) Interior to Lower Mainland (ILM) transmission line, a primary issue during consultation and in the First Nation Interveners’ evidence and submissions before the Commission was the assertion that BCTC/BC Hydro failed to consult on transmission lines, rights‐of‐way, and other assets associated with lines built in the 1960s and 1970s (the “Existing Assets”). The historical infringement of asserted Aboriginal rights permeated the discussions between BCTC/BC Hydro and First Nations. However, following the release of the Court’s decision in Rio Tinto, the First Nation Interveners withdrew their submissions on Existing Assets.60

- The issue also arose in proceedings regarding BC Hydro’s (a Crown agent) proposal to acquire from Teck Metals Ltd. an undivided one-third interest in the Waneta Dam and associated assets. The Waneta Dam is an existing hydro-electric facility that was constructed in the 1950s and has operated ever since. BC Hydro required the approval of the BC Utilities Commission, which was to determine whether the acquisition was in the public interest. In its decision dated March 12, 2010, the BCUC accepted that (i) BC Hydro had a duty to consult; and (ii) the BCUC had to consider the adequacy of that consultation. However, the BCUC rejected the First Nations’ position and BC Hydro was required to consult and accommodate in respect of past infringements and grievances.61 The three First Nation groups all sought leave to appeal the decision of the Commission to the B.C. Court of Appeal on the grounds, inter alia, that the Commission erred in its treatment of the issue of historical infringements. These leave applications were pending (and give a sense of the issues that were pending) at the time the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the Rio Tinto was released. Following the Supreme Court’s decision, all three leave to appeal applications were abandoned.

Following the Rio Tinto decision, it is clear that the focus of Energy Regulators is on the project and application that is before them—the analysis is confined to the adverse impacts flowing from the current decision, not to larger adverse impacts of the project of which it is a part. Subsequent court decisions62 have elaborated or clarified this principle, but not altered it.

Special Issues – To Whom is the Duty to Consult Owed?

Uncertainty regarding the identity of the proper Aboriginal group to be consulted can arise in both a non-treaty or treaty context.

In the May 2013 decision in Behn v Moulton Contracting Ltd, 2013 SCC 26, the Supreme Court of Canada considered the questions of to whom a duty to consult is owed and the proper procedure for bringing a challenge to the adequacy of consultation. The Behns were individual members of the Fort Nelson First Nation. No party brought any legal challenge to the validity of certain forestry authorizations issued to Moulton Contracting Ltd. However, when Moulton attempted to access one of the sites, the Behns erected a camp that, in effect, blocked the company’s access to the logging sites. Moulton commenced a court action. As a defence to that action, the Behns argued that the Authorizations were void because they were issued in breach of the Crown’s duty to consult and because they violated the Behns’ hunting and trapping rights under Treaty No. 8.

The first addressed by the Court was whether the Behns, as individual members of an Aboriginal community, can assert a breach of the duty to consult? The Court confirmed that the duty to consult exists to protect the collective rights of Aboriginal peoples and is owed to the Aboriginal group that holds them. While an Aboriginal group can authorize an individual or an organization to represent it for the purpose of asserting its Aboriginal or treaty rights, no such authorization was given in this case.

Many Energy Regulators, other Crown decision-makers and project proponents have struggled in attempting to discern “who speaks for the Nation” in a consultation process. Many observers had hoped that this decision would provide greater certainty regarding to whom the Crown owes a duty to consult. The Court’s conclusion that the duty “is owed to the Aboriginal group that holds the s. 35 rights, which are collective in nature” provides some clarification.63 However, there remains some legal uncertainty around identifying the Aboriginal group that holds s. 35 rights.

The identity of the proper rights- holder is also a subject that has generated extensive litigation. For example, in William v. British Columbia, 2012 BCCA 285, the BC Court of Appeal recognized that “[w]here there is no body with authority to speak for the collective (or worse, where there are competing bodies contending that they have such authority), consultation may be stymied.”64 However, in the end, the Court of Appeal agreed with the trial judge’s conclusion “that the definition of the proper rights holder is a matter to be determined primarily from the viewpoint of the Aboriginal collective itself.”65 The Supreme Court of Canada heard an appeal from this case in November 2013, and a decision is pending. Accordingly, both legally and factually, there remains residual uncertainty regarding how to identify—in the words of the Behns case—“the Aboriginal group that holds the s. 35 rights” to whom a consultation duty is owed.

The Court in Behn also commented a related issue—whether treaty rights be invoked by individual members of an Aboriginal community? The Court noted that certain Aboriginal and treaty rights may have both collective and individual aspects, and it may well be that in appropriate circumstances, individual members can assert them. However, the Court found it unnecessary to make any “definitive pronouncement” in this regard in the circumstances of this case. The Court’s reluctance to fully address this issue is somewhat disappointing (although understandable) and leaves unanswered (for now) the question of what might be “appropriate circumstances” in which an individual may assert Aboriginal and treaty rights (and whether such circumstances may further require consultation with such individuals). The Court had previously sent signals that individuals were not necessary parties to consultation. In Little Salmon, the Court had considered the position of an individual trapper and concluded that the trappers’ entitlement “was a derivative benefit based on the collective interest of the First Nation of which he was a member” and that “he was not, as an individual, a necessary party to the consultation.”66 The Court’s more open-ended discussion in Behn ensures that further litigation on this point is all but inevitable.

Part II Conclusion

In summary, while many important questions have been answered and many “details” have been filled in on the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate, many equally large and important questions remain to be resolved. Such further clarity will likely only come—“in the age-old tradition of the Common Law”—in small, incremental steps. While it remains to be seen whether the next ten years of jurisprudence will be as dramatic as the last ten years, there remain an ample number of significant questions still awaiting a definitive pronouncement.

The next Part will address the role of the Energy Regulator in respect of the Crown’s duty to consult. The reach of the regulator is determined and confined by the government (federal or provincial) that created it and thus the jurisdiction of many Energy Regulators is limited or differentiated by provincial/territorial political boundaries. However, as we have discussed in Parts 1 and 2, the various legal contexts applicable to Aboriginal groups (historic treaty, modern treaty or non-treaty) are not confined or limited to provincial or territorial boundaries. A single province may include (and thus a single Energy Regulator may encounter) Aboriginal groups with a historic treaty, modern treaty or no treaty.

Part III – The Role of the Energy Regulator in Respect of the Crown’s Duty to Consult67

The key argument in this Part is that there is no universally applicable answer to the question: What is the role of the Energy Regulator? The answer will depend on the statutory mandate given to the Energy Regulator in the context of the application being considered. As discussed below, some guidance may be had from examining how the regulatory process fits into the overall decision-making process. In addition, the role of the Energy Regulator may differ depending on the nature of the Applicant appearing before it—in particular whether the Applicant is a Crown agent or a private party. This Part will first outline the general principles and then look at three case studies to consider how these principles apply in the context of a number of Canadian Energy Regulators.

The Role of the Energy Regulator – General Principles

In Rio Tinto Alcan, the Court directly addressed the legal principles underlying the role of an Energy Regulator in relation to the Crown’s duty to consult:

“The duty on a tribunal to consider consultation and the scope of that inquiry depends on the mandate conferred by the legislation that creates the tribunal. Tribunals are confined to the powers conferred on them by their constituent legislation … the role of particular tribunals in relation to consultation depends on the duties and powers the legislature has conferred on it.

The legislature may choose to delegate to a tribunal the Crown’s duty to consult. As noted in Haida Nation, it is open to governments to set up regulatory schemes to address the procedural requirements of consultation at different stages of the decision-making process with respect to a resource.

Alternatively, the legislature may choose to confine a tribunal’s power to determinations of whether adequate consultation has taken place, as a condition of its statutory decision-making process. In this case, the tribunal is not itself engaged in the consultation. Rather, it is reviewing whether the Crown has discharged its duty to consult with a given First Nation about potential adverse impacts on their Aboriginal interest relevant to the decision at hand.

Tribunals considering resource issues touching on Aboriginal interests may have neither of these duties, one of these duties, or both depending on what responsibilities the legislature has conferred on them. …”68

This right of the legislature to determine the mandate of a tribunal results in one of four scenarios:

- the Energy Regulator fulfills the role of engaging in consultation;

- the Energy Regulator fulfills the role of adjudicating the adequacy of consultation;

- the Energy Regulator fulfills both of the above roles; or

- the Energy Regulator fulfills neither of the above roles.

When faced with issues regarding the duty to consult, the first task of the Energy Regulator (and those appearing before them) ought to be to determine which of the above scenarios applies. All too often, the debate—both academic and in the hearing rooms—has focused on what role the Energy Regulator ought to play and the legitimacy and/or efficacy of the alternative means by which the Crown can either carry out consultation and/or assess its adequacy. A commonly invoked passage in this regard is the Court’s statement that: “specialized tribunals with both the expertise and authority to decide questions of law are in the best position to hear and decide constitutional questions related to their statutory mandates.”69 However, regardless of who may be in the best position to hear and decide (and it is often a matter of perspective as to who is in the best position), it is clear that, when it comes to the role of the Energy Regulator and the duty to consult, the choice is with the government. The relevant legal inquiry is into legislative intent.

While the legal question may be clear, unfortunately the answer is not always so obvious. In the vast majority of instances, the legislative foundations of today’s Energy Regulators were laid down at a time when the duty to consult was not (as it is today) an issue that attracted much focus. In the absence of explicit guidance, Energy Regulators will have to search for clues in their existing legislative scheme.

Two key indicia are (i) the power to consider questions of law, and (ii) the remedial powers granted to the Energy Regulator.

Both the powers of the tribunal to consider questions of law and the remedial powers granted it by the legislature are relevant considerations in determining the contours of that tribunal’s jurisdiction: Conway. As such, they are also relevant to determining whether a particular tribunal has a duty to consult, a duty to consider consultation, or no duty at all.

….In order for a tribunal to have the power to enter into interim resource consultations with a First Nation, pending the final settlement of claims, the tribunal must be expressly or impliedly authorized to do so. The power to engage in consultation itself, as distinct from the jurisdiction to determine whether a duty to consult exists, cannot be inferred from the mere power to consider questions of law. Consultation itself is not a question of law; it is a distinct and often complex constitutional process and, in certain circumstances, a right involving facts, law, policy, and compromise. The tribunal seeking to engage in consultation itself must therefore possess remedial powers necessary to do what it is asked to do in connection with the consultation…

A tribunal that has the power to consider the adequacy of consultation, but does not itself have the power to enter into consultations, should provide whatever relief it considers appropriate in the circumstances, in accordance with the remedial powers expressly or impliedly conferred upon it by statute.70

It is not relevant to the inquiry to ask whether or not there is some other administrative or regulatory tribunal that can or will fulfill the role. The Crown cannot avoid its duty to Aboriginal peoples by simply choosing to not assign one or both these functions (i.e. carrying out consultation and/or assessing the adequacy of consultation) to a particular Energy Regulator. The Court was clear in Rio Tinto that the honour of the Crown cannot be avoided.

“The fear is that if a tribunal is denied the power to consider consultation issues, or if the power to rule on consultation is split between tribunals so as to prevent any one from effectively dealing with consultation arising from particular government actions, the government might effectively be able to avoid its duty to consult.

…the duty to consult with Aboriginal groups, triggered when government decisions have the potential to adversely affect Aboriginal interests, is a constitutional duty invoking the honour of the Crown. It must be met. If the tribunal structure set up by the legislature is incapable of dealing with a decision’s potential adverse impacts on Aboriginal interests, then the Aboriginal peoples affected must seek appropriate remedies in the courts: Haida Nation, at para. 51.”71

While there may still be legitimate policy debate about where or by whom the duty to consult should be discharged and/or adjudicated, such policy debate should be separate and distinct from any legal debate about whether the Energy Regulator plays any role in carrying out and/or adjudicating the adequacy of consultation. The proper legal question is: What role has the legislature assigned the Energy Regulator?