Introduction

The North American natural gas market in 2013 was a hot topic news item again, as it has taken center stage in a variety of media outlets over the last several years. While a portion of the industries gas news in the previous year for 2012 was highlighted by low natural gas prices that were generally between $2 and $3 per MMBtu, in 2013 the focus was less on prices as price recovered and more on other issues, including the matter of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exports from North America. Of course, the two items are related in that the recent natural gas abundance resulting from the on-going development of shale gas resources is the driving force behind lower natural gas prices, which together with the supply abundance has created opportunities for serving new markets, all while reshaping the market on this continent.

A brief overview of the new phenomenon of supply abundance, which is relevant for both the United States and Canada, is in order. As late as 2008, conventional wisdom held that North American natural gas production would have to be supplemented increasingly by imports of LNG, natural gas in a different form that was necessitated apparently by domestic natural gas supply resource decline, impending shortages, and resulting in higher commodity prices. Far less conspicuously, in places as such as Texas in the Barnett gas shale and in other places in the mid-continent, Louisiana, Oklahoma and the U.S. northeast region in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus basin, a ‘technological break-through’ was taking place that would transform the industry. Through a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, existing technologies were combined together and continually improved, with dramatic results markedly increasing drilling and production efficiencies, reducing costs, and in the end bringing substantial new volumes of natural gas from ‘unconventional’ supply sources to the market. When Navigant released its American Clean Skies natural gas supply assessment in mid-2008, domestic gas production from shale began to overtake imported LNG as the new gas supply of choice in North America.1 This set off what has been a ‘new era’ of gas supply development characterized by ramping rates of shale gas production growth that have shown no let-up since and have resulted in overall gas supply abundance, even surpluses, over the last several years.

Although the bulk of the gas shale development so far has occurred in the U.S., for several reasons it is the key driver of overall North American gas market developments. First, because the North American natural gas market is a truly interconnected, continental market (if not a part of a global gas market at this point) significant natural gas developments in one region can and do have impacts in other regions. As will be discussed later, for example, the sheer magnitude of the new gas production in the Marcellus Shale centred in Pennsylvania and West Virginia has already caused changes in gas flows that can be seen, so far, as far away as in the U.S. Southeast, as well as north, up into Canada, dramatically affecting flow patterns and changing the historically developed relationships and contracting patterns that were developed over a half century or more. Further, Canada itself has discovered that it, too, has huge shale gas and tight gas resources of its own that are poised for development as the shale gas revolution takes hold in Canada. The sheer size of the new resources that have been unlocked in both countries are what is most notable, setting off a new ‘golden age’ of natural gas in North America and leading to the prospects for and the ensuing debate over serving new markets with North American natural gas in the form of LNG via exports to anxiously awaiting international buyers around the world.

UNITED STATES

Gas Supply

The importance of the shale gas revolution in the U.S. would be difficult to overestimate. Shale gas resources are almost totally behind the large increases in recoverable natural gas resource estimates (as well as the increases in actual production). Not only are entirely new gas resource plays being discovered, and then brought into production, but as additional data from producing gas plays is obtained over time, the resource estimates of those active plays have generally ended up being raised in an on-going series of resource re-assessments. Estimates for the Marcellus play, for example, have risen from 50 Tcf in 20082 to 369 Tcf in June 2013,3 as Marcellus production has increased from virtually nothing to over 10 Bcfd (at the wellhead) in the same period.4 By the end of 2013, Marcellus wellhead production actually exceeded 12 Bcfd, constituting 17 per cent of U.S. Lower 48 wellhead production.5 All in a span of only five years.

For the U.S. as a whole, the natural gas resource estimate released by the Potential Gas Committee in April 2013 put total U.S. recoverable gas resources at 2,689 Tcf, up 24 per cent from 2,170 Tcf in its April 2011 release. At the U.S. 2013 demand level of 26 Tcf,6 that is enough natural gas to meet demand for over 100 years. Notably, the PGC’s shale gas estimate increased a full 50 per cent (from 687 Tcf to 1,073 Tcf), while its non-shale resource estimate increased also but only 9 per cent (from 1,484 Tcf to 1,616 Tcf). The most recent estimate of U.S. shale gas recoverable resources adopted by the U.S. Federal Government is actually even slightly higher than the PGC estimate, at 1,161 Tcf.7

U.S Market Dynamics 2013

Driven by the increases in gas resource estimates, total dry U.S. natural gas production reached an all-time high in 2013, increasing from 2012 levels by about 1 per cent to 24.3 Tcf, which exceeded the pre-shale gas U.S. high of 21.7 Tcf in 1973 by 2.6 Tcf.8 Because of constantly improving drilling efficiencies, the increase in production came despite much lower gas drilling rig counts in 2013, following a steady shift to oil-directed drilling over 20129 — to a point where today, the U.S. is the largest gas producer in the world, having passed Russia in 2011. And on the back of the technology break-through for shale gas, the U.S. has even more recently experienced a renaissance of oil production where it has passed Saudi Arabia in 2013 to become the largest oil producer in the world.10 Over just the last five years, total U.S. gas production has grown a full 21 per cent increasing from 20.1 Tcf to 24.3 Tcf, and the situation has not conceivably peaked. In fact, Navigant forecasts U.S. gas production to increase an additional 24 per cent to 29.9 Tcf in 2020 (about 3 per cent CAGR), and then to increase a further 18 per cent to 36.1 Tcf in 2035 (about 1 per cent CAGR).

Consider further the following. Over the course of 2013, shale production levels (at the wellhead) increased 14 per cent, from 30.9 Bcfd in January to 35.3 Bcfd in December.11 A key driver of this increase was the Marcellus Shale, where production increased 50 per cent, from 8.4 Bcfd to 12.5 Bcfd (at the wellhead) at the end of the year to comprise 35 per cent of total shale gas production.12 Another facet of the growth was that gas production from liquids rich plays increased as producers shifted drilling away from dry gas plays. A prime example of such production is the Eagle Ford shale in south Texas, where gas production grew 39 per cent during 2013, from 3.3 Bcfd in January to 4.5 Bcfd in December.13 Shale gas’ share of total U.S. production (at the wellhead) increased 5 percentage points over the year, from 43 per cent to 48 per cent of Lower 48 total wellhead production.14 For North America as a whole, we estimate unconventional gas made up 35 per cent of dry gas production in 2013, and we forecast more importantly for unconventional gas to grow to 58 per cent of the overall supply mix in 2035.15

U.S. total natural gas consumption in 2013 grew modestly by about 2 per cent, increasing from 25.4 Tcf in 2012 to reach 26.0 Tcf. Compared to 2012, the residential, commercial and industrial sectors each increased consumption (by 21 per cent to 5.0 Tcf, by 13 per cent to 3.3 Tcf, and by 3 per cent to 7.4 Tcf, respectively), while the electric generation sector somewhat surprisingly decreased consumption by 10 per cent. Despite its decrease, electric generation remained the largest gas consuming sector in 2013, with its 8.1 Tcf comprising about 31 per cent of total natural gas consumption. Electric generation gas demand was down in 2013 as a result of higher gas prices than the banner year of 2012 (when electric generation gas demand increased 20 per cent), but over the prior eight years from 2003 through 2011 electric generation demand grew at an average CAGR of 4.98 per cent per year and by 47.5 per cent over the period.

The decrease in natural gas consumption for power generation in the U.S. was driven by the generation resource mix moving from 37 per cent coal and 30 per cent gas in 2012 to a place in 2013 where coal fired generation actually made up 39 per cent of the electric generation sector and natural gas’ share dropped to 27 per cent of the electric generation market in 2013.16 The rebound in coal generation in 2013 is a function of the continuing competitive price structure between the two fuels in some U.S. regions. It is also a function of the delay of various carbon taxes in the U.S. that are expected to increase gas-fired generation compared to coal-fired generation should they occur. In any event, the rebound in coal’s share of the generation mix in 2013 is not assured to continue and may be viewed in hindsight as an anomaly. Looking back over a somewhat longer period, coal has not regained close to its market share of the electric generation sector before the large drop in gas prices in 2012, when coal made up 42 per cent of the electric generation market and gas was at 25 per cent of the electric generation market in 2011. In looking forward, planned coal-fired generation retirements as of January 2014 are expected to total 34,000 MW, which is an increase from mid-2012 forecasts of planned retirements of about 31,500 MW, and should again result in the eventual growth of gas fired generation at the expense of coal in the electric generation sector in the U.S.17 Our firm’s forecast of the future generation mix (like other’s I have seen at least directionally) is for coal to decrease from a 39 per cent market share in 2014 to a 35 per cent market share for coal in 2018, as large amounts of coal-fired generation retire.

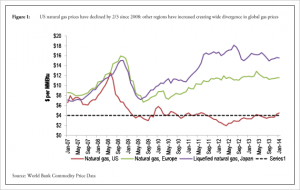

The annual average spot price in the U.S. national market measured at Henry Hub was up 35 per cent in 2013, to $3.73/MMBtu versus $2.75/MMBtu on the same basis in 2012. This, I might point out, was still 7 per cent below annual prices in 2011 that were $4.00/MMBtu.18 To put current U.S. gas prices in perspective, $3.73 is actually 58 per cent below the average annual spot price in 2008 of $8.86/MMBtu, before the shale revolution. Notably, this level is also well below gas prices in other parts of the world, such as in Europe with gas prices averaging $11.79/MMBtu and in Japan with gas prices averaging $16.02/MMBtu in 201319 (see figure 1 below). Of course, it is this huge price differential between domestic U.S. and North American natural gas prices, due to gas supply abundance, and prices in the international market that are yet to experience the impact of shale gas and are in some cases pegged to high priced oil, that creates opportunities for economically-driven LNG exports – a matter that became increasingly important in the U.S. gas market in 2013.

U.S. LNG Exports to Global Gas Markets

There was significant activity at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Fuels (DOE) in 2013 regarding applications for authorization to export LNG to Non-Free-Trade nations.20 The year started off with the DOE taking scores of comments from interested parties on its LNG Export Study, the second and final piece of which (the NERA Report) was released in December 2012.21 Key findings of the NERA Report were that LNG exports will create net economic benefits to the country, and that the global modelling used in the report actually showed that many assumed levels of LNG exports (i.e. the higher ones) used in the initial part of the LNG Export Study (the EIA Report) would not be economically feasible in the global market, and therefore would lead to invalid results should they be assumed as parameters in a North American model. These findings in favour of LNG exports were subsequently relied on by DOE as it started to move forward with its backlog of LNG export authorization applications. While the last prior LNG export authorization had been granted almost two years earlier (and in fact was the first non-FTA authorization and export approval by the DOE and was supported in the application by Navigant),22 within three months after the comment period on the LNG Export Study ended the DOE issued its next authorization, to Freeport LNG, in May 2013.23,24 Following the Freeport authorization, DOE followed with additional approvals for Lake Charles LNG (August), Cove Point LNG (September), and Freeport Expansion LNG (November). On February 11, 2014, the DOE approved Cameron LNG, LLC’s application to export up to 1.7 Bcfd to non-FTA countries for a period of twenty years. The DOE has now issued non-FTA LNG export authorizations for about 8.5 Bcfd in aggregate.

At present, the remaining non-FTA LNG export applications total about 26 Bcfd from almost twenty projects, with 11.6 Bcfd having been filed in 2013 by eight projects. DOE has created an “order of precedence” for its review of the applications, which is basically the order of filing of the respective DOE applications (provided that a project had received approval from FERC to utilize FERC’s pre-filing process for site approval by December 5, 2012). The next five applications up for review, according to the DOE’s order of precedence are: i) Jordan Cove Energy Project, 0.8 Bcfd from Oregon; ii) Oregon LNG, 1.0 Bcfd from Oregon; iii) Corpus Christi Liquefaction, 1.8 Bcfd from Texas; and iv) Excelerate Liquefaction Solutions, 1.4 Bcfd from Texas; Carib Energy (USA) LLC, 0.03 Bcfd from Texas (see figure 2 below). With respect to the ultimate level of LNG export capacity that is likely to be built in North America, and regardless of the volumes ultimately permitted by the DOE, Navigant’s view is that U.S. exports will likely be in the 8 to 10 Bcfd range, much less than the total application volumes or possibly even the volume ultimately given approval by the DOE. A number of factors contribute to this view, including the fact that substantial capital requirements are necessary for each project, the significant commercial contractual issues to be resolved, and that the existence of global competition from existing large LNG exporters such as Qatar and Australia as well as emerging potential projects around the globe from places like East Africa and other areas in the Middle East, and indeed the emergence of competition through development of global shale resources, especially in emerging market regions around the world.25

Of the five projects that now hold U.S. non-FTA LNG export approvals, only the Cheniere Corporation’s Sabine Pass Liquefaction facility has also received the necessary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) site approval and is under construction. The first phase of that project, comprised of Trains 1 and 2 of about 0.55 Bcfd each, is over 50 per cent completed as of December 2013. Construction work on Trains 3 and 4 (Phase 2) is also under way, and is about 20 per cent completed.

Many significant LNG commercial arrangements have already been signed by the LNG export projects. Publicized agreements from 2013 include: those between Cameron LNG and Tokyo Electric Power Company, GDF Suez, Mitsubishi, and Mitsui; those between Freeport LNG and Osaka Gas, Chubu Electric Power, BP, and Toshiba; and between Sabine Pass and Centrica. Prior publicized agreements include: those between Sabine Pass and Total, GAIL, Kogas, Gas Natural Fenosa, and BG; those between Cove Point LNG and Gail and Sumitomo; and between Main Pass LNG and Petronet. As North American supplies become increasingly important to overseas buyers and by so doing moves the market towards a truly “global market” the likelihood is that the market will be characterized by ongoing weakening of oil-indexed gas pricing that is now dominant in both Asia and Europe. Some weakness regarding ‘oil-indexing’ has already shown up in contract negotiations and renegotiations that have already taken place in Europe, as has been reported by several ‘insiders’ spoken to at a recent European gas conference. Such fundamental changes in the global gas landscape will be one of the major developing stories in the years to come, but first became apparent in the market in 2013.

CANADA

Gas Supply Resources

Similar to the case of U.S. recoverable gas resource estimates, Canadian gas resource estimates have shown large increases recently. A key component of the increase is the new estimate of gas resources for the Montney formation in Alberta and British Columbia. A November 2013 joint report of the National Energy Board, the British Columbia Oil & Gas Commission and Ministry of Natural Gas Development, and the Alberta Energy Regulator that singled out a review for the Montney, increased the estimate of recoverable natural gas in the Montney from 108 Tcf to 449 Tcf, which the report’s website noted would leave the revised Montney formation alone able to meet Canadian demand for 145 years.26 Another key driver is the latest detailed estimate of shale play resources as contained in the ARI assessment commissioned by the EIA and released in May 2013. The ARI Report put Canadian shale gas recoverable resources at 573 Tcf, including the Horn River at 133 Tcf, the Liard Basin at 158 Tcf, the Duvernay at 113 Tcf, and the Cordova Embayment at 20 Tcf.27 Adding the 449 Tcf for the Montney and the 573 Tcf for shale gas to the 422 Tcf for non-shale and non-Montney natural gas resources as most recently estimated by the NEB,28 yields estimated total Canadian recoverable resource at 1,444 Tcf, a staggering 465 years of Canadian demand at the 2012 level of 3.1 Tcf per year total gas consumption level used by the NEB.

Canadian Market Dynamics in 2013

Canadian total marketed gas production decreased about 1.5 per cent in 2013, dropping from 5.05 Tcf to 4.97 Tcf. The drivers were a two per cent decrease in Alberta, from 3.48 Tcf to 3.41 Tcf, coupled with a three per cent increase in British Columbia, from 1.29 Tcf to 1.33 Tcf.29 The most active areas of developing production were the Montney formation, with 2.4 Bcfd (2.05 Bcfd in B.C. and 0.35 Bcfd in Alberta), and the Horn River basin, with 0.5 Bcfd, as of the third quarter of 2013.30

With the increase in shipments of Marcellus gas to U.S. markets, exports of Canadian natural gas into the U.S. fell 12 per cent from 2012 to 2013 (measured over the first 10 months of the year), dropping from 5.77 Bcfd to 5.05 Bcfd.31 This is yet another shining example of the ‘game changer’ aspects brought about by a technical breakthrough that has taken over the integrated North American gas industry over the last five years.

In 2013, the annual average spot price (at AECO) was up 28 per cent in 2013, to $3.06/MMBtu32 versus $2.39/MMBtu in 2012, but still 17 per cent below the same price in 2011 of $3.67/MMBtu. Obviously some equilibrium adjustments are still occurring in the Canadian gas industry as they are in the U.S., with gas price in North America well below gas prices in other parts of the world, such as in Europe where as we have said gas prices averaged $11.79/MMBtu and in Japan where prices averaged $16.02/MMBtu in 2013.33 It is also worth noting that Canadian prices are below U.S. gas prices in most markets due to the particular high levels of supply abundance and the fact that supply in some instances is stranded as a result of changing market dynamics affecting Canadian gas supply.

Canadian LNG Export Developments

As in the U.S., there was significant activity in Canada in 2013 related to LNG exports. While the NEB had approved two export applications over the prior two years, totalling 1.55 Bcfd,34 in 2013 the NEB approved four LNG export applications, totalling 13.1 Bcfd.35 A consistent theme in the NEB’s approval orders was the recognition that the sheer magnitude of Canadian natural gas resources, together with the new North American market dynamics driven by increasing U.S. natural gas production, making it important for Canada to find new markets to support further development of its domestic gas industry.36

At present, the remaining gas export applications to the NEB total 10.7 Bcfd from six projects, all filed since August 2013, and all but 1.4 Bcfd from the west coast of Canada. Two of the applications, by Jordan Cove LNG and Oregon LNG Marketing, are by proposed U.S. LNG liquefaction projects that will rely upon Canadian natural gas feedstock, to be delivered in large part through the long standing existing interconnected pipeline grid that exists in the region and supporting the projects. These applications are an indication of the abundant endowment of natural gas in Western Canada, and are an example of the type of new market the provinces of B.C. and Alberta are seeking in order to bolster their own gas industries.

Infrastructure Developments

Another important set of 2013 natural gas developments are those affecting the TransCanada Corporation, one of North America’s largest gas pipeline companies and a long standing and important artefact of the Canadian gas industry. Several events relate to TransCanada’s mainline, with capacity to move 7 Bcfd from Empress, Alberta to Dawn, Ontario and farther eastward. In 2013, the NEB approved new reduced mainline rates proposed in a major rate restructuring application aimed at improving the competitiveness of the mainline given its decreasing throughput, which for some time had been causing rate increases on the system. The new rates that were set from Empress to Dawn delivery are $1.42/GJ, down from the old rate of $2.58/GJ, and based on throughput expected to increase from 3.9 Bcfd to 4.3 Bcfd. A second important development in 2013 occurred as TransCanada announced in August that it will move forward with its Energy East project, a project that would convert about 1 Bcfd of Mainline capacity from natural gas to oil transportation and is viewed by TransCanada as an attempt to ‘utilize’ otherwise surplus capacity on its Mainline.

Other events impacting other parts of TransCanada’s business in Canada include: i) selection by Progress Energy’s Pacific Northwest LNG in January 2013 to build the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission project to move 2 Bcfd of natural gas from the North Montney area to the LNG project on Lelu Island near Prince Rupert; ii) execution of a contract in August with Progress Energy for about 2 Bcfd of firm gas transportation service that will help move forward its NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. subsidiary’s North Montney mainline project; iii) proposed enhancement by FortisBC of the Southern Crossing Pipeline linking Spectra Energy’s system at Kingsvale to Kingsgate, that will provide additional capacity for natural gas to get from the Spectra system in B.C. onto TransCanada’s GTN system to serve the U.S. Northwest and California markets and possibly to serve export projects in Oregon.

Demand Expansion Policy

Consistent with the NEB Short-Term Deliverability report37 showing Canadian natural gas production in a “holding pattern” with minimal new drilling activity as producers wait for natural gas prices to increase, finding new or expanded markets for natural gas has been a newly developed yet now entrenched new policy direction in Western Canada. In July 2013, the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta announced the formation of a Working Group led by senior energy officials to develop recommendations related to energy exports, towards opening new export markets for B.C. and Alberta.38 The shared goals of B.C. and Alberta in creating the Working Group are to expand export opportunities for oil, gas and other resources, and to create jobs and strengthen the provincial economies through the development of the oil and gas sector. The Working Group reported to Premieres Clark and Redford at the end of 2013 with recommendations and an action plan. The creation of the Working Group indicates the clear policy support for gas resource development.39 In a similar vein, Alberta executed in October 2013 a Framework Agreement on Sustainable Energy Development with China to strengthen ties in energy development, energy investment and energy trade.

2013 in Summary

The phenomenon of North American natural gas abundance due to the shale revolution continued in 2013. U.S. production advanced to a new all-time high, and the U.S. DOE moved forward with four LNG non-FTA export approval orders (with a fifth Cameron LNG approved early in 2014). The abundance of natural gas that is evidenced by the prolific growth in shale gas production, such as the 50 per cent growth in Marcellus Shale production during 2013, has only been further enhanced by updated resource studies indicating about 2,700 Tcf of recoverable gas in the U.S. and over 1,400 Tcf in Canada. The dependability of shale gas production as a result of its abundance, as well as its reduced exploration risk as compared to conventional gas resources, creates the potential to improve the alignment between supply and demand and mitigate the industry’s “boom and bust” cycles, which will in turn tend to lower price volatility, a long standing issue for the gas industry that has hampered increased market penetration. Thus, the vast shale gas resource not only has the potential capability to support a much larger demand level that has yet been seen in North America, but at prices that are less volatile and indeed at lower overall price levels than were thought possible just a few years ago.

An informed market view is that U.S. and Canadian domestic supply is abundant to such a degree that it will support domestic market requirements as well as export demand for LNG shipped from North America. Indeed, the new environment of gas abundance not only enables but is in need of new market demand that will offer the potential for a steady, reliable baseload market to underpin future supply development. As evidenced by the many LNG export applications filed, industry players recognize the opportunity that currently exists due to the current differentials in world gas prices. The opportunity for LNG exports from U.S. and from Canada, however, will yield benefits far beyond the gas industry, providing benefits to the overall economy through multiplier effects that create additional indirect economic stimulus impacts from the billions of dollars in new investment and through job creation.

The magnitude of shale gas production, particularly in Eastern U.S., started to cause dramatic and fundamental changes in traditional gas flow patterns across North America in 2013.40 A prime indicator of this dynamic is the change in supply patterns to the U.S. Northeast market, where Marcellus Shale production has displaced supplies from both the U.S. Gulf region and the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, resulting in reductions of market share by a 28 per cent share (from a 50 per cent share to a 22 per cent share, a 56 per cent reduction) and a 15 per cent share (from a 22 per cent share to a 7 per cent share, a 68 per cent reduction), respectively, since 2008. Canada’s National Energy Board has recently recognized these new market dynamics in Energy Future 2013, referencing increasing production from the Marcellus that has reduced the need for Canadian exports to the U.S. Northeast, a market traditionally served in part by WCSB gas,41 and in fact has led to increasing imports into Canada from the U.S.42 that is expected only to continue to increase in the future. I believe additional competitive pressure on Western gas supplies will result from Marcellus and Utica Shale gas displacing traditional supplies in the U.S. Midwest market, which could be Canadian WCSB gas or U.S. Rockies gas that could ultimately put pressure upon Canadian supplies further west as the U.S. Rockies gas seeks new markets. An example of changing flow patterns across North America is that the Rockies Express Pipeline executed a binding precedent agreement in July 2013 to move up to 200 MMcfd of a large Utica Shale producer’s gas westward to midcontinent markets. REX noted that it anticipates becoming “truly bi-directional” as it provides takeaway capacity from the Utica Shale.43 The initial signs of other flow pattern changes across North America also started to become clearer in 2013 – driven by new shale gas development.

With increasing pressure on Western gas supplies due to the remarkable development of Eastern U.S. resources, the need for new markets for Western gas will be even more dramatic as the prolific unconventional gas resources in British Columbia are developed, creating what I would suggest will be a groundswell of commercial opportunities, particularly in Western Canada. I furthermore expect this market change that developed clearly in 2013 to continue to develop over the foreseeable future as Asian markets discover the benefits and alignment of LNG supply from North America with Asian growth in gas demand.44

* Gordon Pickering, Navigant Consulting, Inc. is a Director, Energy and lead of Navigant’s North American Natural Gas and LNG practice. He is active in gas and LNG commodity pricing, strategy, regulatory, fundamental market analysis and forecasting in North America and internationally.

1 Navigant first quantified the rapidly expanding development of natural gas from shale in 2008, in its ground-breaking report for the American Clean Skies Foundation, North American Natural Gas Supply Assessment (4 July 2008), online: Navigant Consulting

<http://www.navigant.com/~/media/WWW/Site/Insights/Energy/NCI_Natural_Gas_Resource_Report.ashx>.

2 Terry Endelger & Gary G. Lash, “Marcellus Shale Play’s Vast Resource Potential Creating Stir in Appalachia” (May 2008), online: American Oil & Gas Reporter <http://www.aogr.com/index.php/magazine/cover-story/marcellus-shale-plays-vast-resource-potential-creating-stir-in-appalachia>.

3 World Shale Gas and Shale Oil Resource Assessment, prepared by Advanced Resources International, Inc. as exhibit to Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States, U.S. Energy Information Administration, June 2013, Attachment C, Table A-1.

6 US Energy Information Administration, Natural gas consumption by End Use (28 February 2014), online: EIA <http://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_cons_sum_dcu_nus_a.htm>.

7 See ARI Report, supra note 3, Attachment C, Table A-1.

8 US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data.

9 Navigant estimates average U.S. gas rig counts of 556 in 2012 and 383 in 2013, based on Baker Hughes data.

10 See “Today in Energy: U.S. expected to be largest producer of petroleum and natural gas hydrocarbons in 2013”, www.EIA.gov, October 4, 2013.

12 Ibid 12.5 Bcfd Marcellus wellhead production versus 35.3 Bcfd Lower 48 wellhead shale gas production in December 2013.

14 Ibid,30.9 Bcfd shale wellhead production versus 71.1 Bcfd Lower 48 wellhead production in 2012; 35.3 Bcfd versus 73.7 Bcfd in 2013.

15 Gordon Pickering & Rebecca Honeyfield, “North American Natural Gas Market Outlook, Fall 2013” (1 December 2013) at p 3, online: Navigant Consulting Perspectives <http://www.navigant.com/insights/library/energy/2013/ng-outlook-fall-13/> .

19 World Bank Commodity Price Data. See figure 1 above.

20 Approval of exports to countries with a Free Trade Agreement with the U.S. is almost ministerial and automatic. There are currently 20 countries with a Free Trade Agreement, the only one of which is a major LNG-importing nation being South Korea.

21 Macroeconomic Impacts of LNG Exports from the United States, NERA Economic Consulting, December 2012. The initial component of the LNG Export Study was performed by EIA, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Effect of Increased Natural Gas Exports on Domestic Energy Markets, January 2012.

22 DOE/FERC Order No 2961, Opinion and Order Conditionally Granting Long-Term Authorization to Export Liquefied Natural Gas From Sabine Pass LNG Terminal to Non-Free Trade Agreement Nations, May 20, 2011.

23 DOE/FERC Order No 3282, Order Conditionally Granting Long-Term Multi-Contract Authorization to Export Liquefied Natural Gas by Vessel From The Freeport LNG Terminal on Quintana Island, Texas to Non-Free Trade Agreement Nations, May 17, 2013.

24 For an analysis of FERC’s LNG export approvals, see Gordon Pickering and J. Van Horne, “Why a Market Solution to the LNG Export Question Makes Sense” NG Market Notes (June 2013), online: Navigant Consulting,<http://www.navigant.com/insights/library/energy/2013/ng-market-notes-june-2013/>.

26 The Ultimate Potential for Unconventional Petroleum from the Montney Formation of British Columbia and Alberta, Energy Briefing Note, National Energy Board, B.C. Oil & Gas Commission, Alberta Energy Regulator and B.C. Ministry of Natural Gas Development, November 2013. Note that although portions of the Montney Formation are shale gas, the formation as a whole is generally classified as unconventional but non-shale due to the variety of its characteristics, including tight gas. See FAQs at <http://www.neb-one.gc.ca/clf-nsi/rnrgynfmtn/nrgyrprt/ntrlgs/ltmtptntlmntnyfrmtn2013/ltmtptntlmntnyfrmtn2013fq-eng.html>.

27 See ARI Report, supra note 3, Attachment A.

28 See Canada’s Energy Future 2013: Energy Supply and Demand Projections to 2035, National Energy Board, November 2013 at 49.

30 Ibid.

33 World Bank Commodity Price Data (Pink Sheet), online:

http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/EXTDECPROSPECTS/

0,,contentMDK:21574907~menuPK:7859231~pagePK:pagePK:64165401~piPK:64165026~

theSitePK:476883,00.html

34 Kitimat LNG (1.3 Bcfd) in 2011 and BC LNG (.25 Bcfd) in 2012.

35 LNG Canada (3.2 Bcfd), Pacific Northwest LNG (2.7 Bcfd), Prince Rupert LNG (2.9 Bcfd), WCC LNG (4.0 Bcfd) and Woodfibre LNG (.29 Bcfd)

36 See e.g., NEB, Letter Decision for WCC LNG Ltd, OF-EI-Gas-GL-W156-2013-01 01 (16 December 2013).

37 National Energy Board, Short-Term Canadian Natural Gas Deliverability, 2013-2015, May 2013 at1.

38 See British Columbia/Alberta Deputy Ministers Working Group “Terms of Reference”, (26 July 2013), online: BC government <http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/15/ks-tallgrass-energy-idUSnBw156415a+100+BSW20130715>.

39 The formation of the Working Group follows the release in February 2012 of the clearly stated, progressive and unique policy of the province of British Columbia, as part of the overall Province Jobs Plan, in favour of accelerated development of its natural gas resources. In its Natural Gas Strategy document, as well as a complementary Liquefied Natural Gas Strategy, the province presented its goals of building three LNG export facilities by 2020, and estimated an accompanying increase in gas production from the current level of 1.2 Tcf per year to over 3 Tcf per year in 2020. Further, the Strategy included the diversification of its gas markets, including development of supplies to meet new gas demand in North America. With these natural gas and LNG strategies, the province has clearly been planning for a significant growth of its natural gas industry, from upstream production through midstream transportation and processing, to further growth of downstream end-use markets.

40 See e.g. Rebecca Honeyfield, “Shifting Gas Flows” NG Market Notes (9 September 2013), online: Navigant Consulting, <http://www.navigant.com/insights/library/energy/2013/ng-market-notes—september-2013/> .

41 See National Energy Board, Canada’s Energy Future 2013: Energy Supply and Demand Projections to 2035- An Energy Market Assessment, (November 2013), at 15.

43 Rockies Express Pipeline LLC, Press Release, “Shale to Shining Shale Strategy” (15 July 2013), online: Reuters <http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/15/ks-tallgrass-energy-idUSnBw156415a+100+BSW20130715>.

44 This expectation would be further supported by associated gas that is likely to be produced from California’s prolific Monterey Shale oil resource as it develops. According to EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2013 Assumptions (Table 9.3), the Monterey oil shale play is the largest in the country, with 13.7 billion barrels of oil, actually exceeding the sum of the Bakken (8.0 billion barrels) and the Eagle Ford (5.2 billion barrels).