Introduction

The emergence of shale production as an important component of natural gas supply in the United States has markedly altered the operating environment of the North American gas industry over the last decade or so. Prior to that, the frequently discussed, but yet-to-be-realized, potential of liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports into the United States attracted much attention from market analysts and policy-makers alike. Throughout all this, Canada remained by far the most important “foreign” source of natural gas supply for US buyers. The relative importance of imports in meeting US consumption needs, however, has fallen in recent years as US production of shale gas has continued to grow. And Canadian natural gas production has not continued to grow at the rates observed between the mid-1980s and the early 2000s.

The main objective of this paper is to consider whether the developments identified above have led to changes in the perceived future role of Canadian natural gas in the United States. How important a role is Canadian-produced gas expected to play in meeting future US natural gas consumption? How do projected LNG trade and US shale gas production affect the prospects for Canadian natural gas in the United States in the longer term? Consideration of these and related questions are at the heart of the matters to be addressed in this paper.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. The next section provides information about the evolution of specific elements of natural gas markets in Canada and the United States. This information sets the context for the following section which examines projections of the role of Canadian-produced natural gas in the United States. The sources of the projections considered are the 1997 to 2014 editions of Annual Energy Outlook, a product of the Energy Information Administration, an agency of the US Department of Energy. The next section then offers reflections on implications for Canada and for gas markets in North America of the factors that underlie changes in the expected role of Canadian-produced natural gas in the United States revealed by the EIA projections. A concluding section brings together the key findings of the paper.

Elements of Context

In the second half of the 1980s, the operating environment of Canada’s natural gas industry was radically transformed. In a matter of a few short years, an industry characterized by tight regulation (including export price and volume controls) and merchant pipelines became one that was anchored on wholesale transactions (including on export markets) at terms governed by individual buyers and sellers and open-access pipelines. This story has been told a number of times already, so there is no need to repeat it here.2 For the purposes of this paper, however, a key point to note is that this push toward a less regulated operating environment was followed by a period of phenomenal growth of natural gas production and exports.

As shown in Figure 1, production in 1986, for example, had been only slightly higher than that realized in 1980: 2.54 vs 2.46 trillion cubic feet (TCF), respectively.3 And most of this gas was consumed in Canada. In every year from 1980 to 1986, domestic use (defined as production plus imports minus exports) accounted for more than two-thirds of total gas production in Canada.

In contrast, production grew by slightly more than 46 per cent (to 3.72 TCF) between 1986 and 1992 – an equal span of six years. Indeed, Canadian production of natural gas continued to grow strongly for another decade. By 2002, production reached 6.08 TCF, more than double that achieved in 1986. In the fifteen years that separate 1987 from 2002, output of natural gas from Canadian sources rose at an average rate of 5.4 per cent per year.

Over the same period, natural gas use in Canada also grew, but more slowly, rising from 1.78 TFC in 1987 to 2.51 TCF in 2002 – an average annual growth rate of 2.3 per cent. Growth in export volumes was even stronger than growth in production. From 1987 to 2002, exports of Canadian-produced natural gas to the United States – the sole export destination available to Canadian producers – rose from just below 1.0 to 3.80 TCF – an annual rate of increase of 9.4 per cent. The share of Canadian natural gas production consumed domestically fell rather consistently throughout this period, reaching 41.3 per cent in 2002. Figure 1 shows quite clearly the pronounced and sustained growth experienced in the output of Canada’s natural gas industry during that period. It is also clear from Figure 1 that until 2000, natural gas imports into Canada were negligible. While there was then a slight increase in the next two years, import volumes remained quite small, reaching about 6 per cent of export volumes in 2002.

Figure 2 shows information on US natural gas consumption, production (dry gas production is the measure used here) and trade with Canada over the same 1980-2013 period as in Figure 1.4 The US natural gas industry underwent a process of deregulation similar in nature to what occurred in Canada. The US process, however, began earlier and lasted longer: it started in the late 1970s and was arguably not completed until the early 1990s. Nonetheless, to facilitate comparisons with developments in Canada, let us first focus on the 1980-1986 period. Overall, US natural gas production fell by approximately 17 per cent during those years, reaching its lowest value of 16.1 TCF in 1986. Imports from Canada – or anywhere else for that matter – did not play a big role in meeting US consumption between 1980 and 1986, accounting for some 4.6 per cent of domestic needs by the end of that period. In volumetric terms, imports from Canada were relatively flat: going from 0.80 TCF in 1980 to 0.74 TCF in 1986. Exports to Canada (or, again, anywhere else) were negligible during this period: net imports from Canada (i.e., gross US imports from Canada minus gross US exports to Canada) effectively equalled (gross) imports.5 Between 1980 and 1986, the story of natural gas in the United States can thus be described as a period of contraction in production and consumption, and sluggishness in trade.

Things began to change in 1987 as growth in US consumption started to pick up and to outstrip that of domestic production. Between 1987 and 2002, US consumption grew by 33.7 per cent (from 17.2 to 23.0 TCF), while US production grew at less than half that rate, rising from 16.6 to 18.9 TCF, or 13.9 per cent, over the course of the same period. As Figure 1 indicates, imports from Canada filled this growing gap between US natural gas use and domestic production. In 2002, import volumes from Canada reached 3.79 TCF, the highest value for this period, and accounted for 16.5 per cent of total US natural gas consumption. US exports to Canada did grow over that period, but still amounted to only 0.19 TCF in 2002, only a small fraction of the trade flow going in the opposite direction.

The situation in 2002 can thus be characterized as follows. Canadian natural gas production has been rising rapidly over the previous fifteen years. Growth in exports to the United States has been even stronger as Canadian producers moved to fill the gap between US consumption and production. Overall, Canada has become an important source of natural gas for US consumers, while there continues to be very limited penetration of US-produced gas in Canada. Readers will have noted, of course, that the integration of Canadian and US natural gas markets became even more pronounced between 1987 and 2002, helped by the 1985 Halloween Accord in Canada, that deregulated natural gas markets in Canada, and with the coming into effect of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in 1989 and the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. As a result, any changes in natural gas trade patterns between Canada and the United States occurring after the mid-1990s are unlikely to be linked to trade policy changes in either country. Instead, market forces and thus the actions of market participants effectively determine flows of natural gas between these two countries. By 2002, Canada is thus an important, secure, and reliable source of natural gas supply for the United States, a state of affairs that had been solidified over the course of the previous fifteen or so years as a result of earlier policy actions and as the outcome of decisions by buyers and sellers of natural gas in the two countries.

And then the situation started to change again, as Figures 1 and 2 indicate. Production in both Canada and the United States was relatively flat for the ensuing five or so years, beginning in 2002. Exports of Canadian-produced natural gas to the United States also stayed relatively constant, but imports from the United States, though still relatively small, grew sharply (see Figure 1): between 2002 and 2007, Canadian imports of US-produced natural gas (mostly in Eastern Canada) more than doubled, reaching 0.48 TCF at the end of this period. During this period, growth in Canadian consumption was uneven, such that by 2007 domestic use was effectively the same as it had been in 2002 (2.48 vs. 2.51 TCF, respectively).

After this short “pause”, the situation began to evolve in markedly different ways in the two countries. Production in the United States was on a sharp upward trend, growing by 26 per cent between 2007 and 2013. In contrast, Canadian production was edging downward, falling by some 14 per cent over the same period. By 2013, US natural gas production reached 24.3 TCF, a historical peak. Meanwhile, at 4.99 TCF, Canadian production in that year was almost exactly equal to the levels achieved 20 years earlier: in 1994, production of natural gas in Canada had been 4.90 TCF. As Figure 1 shows, Canadian consumption grew during this period, rising from 2.48 TCF in 2002 to 3.02 TCF in 2013 – in this last year of the time period under consideration, domestic use of natural gas in Canada exceeded exports to the United States for the first time. Canada also became much more reliant on the United States as a source of natural gas to meet domestic (here, Canadian) consumption needs: by 2013, volumes imported from the United States amounted to 31.7 per cent of Canadian natural gas use – that proportion had been equal to just 9.3 per cent in 2002.

All of a sudden US-produced natural gas was meeting consumption needs both domestically and in Canada. As an examination of Figure 2 reveals, US production grew faster than domestic consumption, meaning that the wedge between US consumption and production had been closing for the last half dozen years or so by the end of the period under consideration. Between 2007 and 2013, exports of US-produced natural gas to Canada almost exactly doubled, rising from 0.48 to 0.94 TCF. Perhaps not surprisingly, Canadian exports to the United States fell markedly during these six years, from 3.83 TCF in 2007 to 2.91 TCF in 2013 – a drop of almost 25 per cent. When brought together, these last two elements imply that the fall in net exports of natural gas from Canada was even more pronounced than that in (gross) exports: from 3.35 to 1.97 TCF – a reduction of about 40 per cent ‒ over that time period. By 2013, net imports of natural gas from Canada met approximately 7.2 per cent of US natural gas consumption requirements, whereas the comparable measure for 2007 had been almost exactly double that value at 14.3 per cent.

By 2013, and the end of the period under consideration, the natural gas industry faced different realities in Canada and the United States. After a period of decrease, Canadian production had stabilized, but exports continued to fall, while imports from the United States were now a not insignificant part of Canada’s energy consumption landscape (especially in Eastern Canada). US natural gas production, on the other hand, had reached historical highs and had grown faster than domestic consumption, thus resulting in a sharply narrowed gap between US consumption and production. Imports volumes from Canada had fallen sharply which, combined with the growth in US exports to Canada, meant that once adjustments had been made for offsetting trade flows, Canadian-produced natural gas played a much smaller role in meeting US consumption needs. As was the case in 2002, Canada continued to be a secure and reliable source of natural gas supply for the United States in 2013. In contrast to the situation prevailing a dozen or so years earlier, however, in 2013 Canada was a much less important source of supply for US consumers of natural gas, in both relative and absolute terms: export volumes from Canada were lower and accounted for a smaller proportion of US consumption than had been the case in 2002.

Since the advent of natural gas deregulation in Canada in the mid-to-late-1980s, we can thus identify two distinct “periods” – and a brief transition between the two – in Canadian and US production and in natural gas trade between the two countries. From the mid-1980s to the turn of the century, Canadian production rose faster than that in the United States where the growth in consumption exceeded that of domestic production. Canadian producers moved in to fill this widening gap. Natural gas trade between the two countries was essentially a one-way flow, with volumes going from Canada to the United States. Canadian-produced natural gas met a rising proportion of US consumption needs.

The period from 2002 to 2006 can probably best be characterized as a transition phase for natural gas production and trade in North America. Natural gas production in both countries was relatively unchanged. Exports of Canadian-produced natural gas to the United States plateaued as well. Canadian import volumes of US-produced gas grew slightly, but remained relatively small. The stage was set, however, for pronounced changes in the structure of natural gas production and trade in North America.

Beginning in 2007 and lasting at least until the end of the period under consideration (i.e., 2013), Canadian and US production patterns differed sharply, with a rising trend characterizing the latter and falling production being observed in Canada. US natural gas production is rising faster than domestic consumption and Canadian exports to the United States are falling. US exports to Canada, while still smaller than trade flows in the other direction, are rising. Canadian-produced natural gas meets a shrinking proportion of US consumption needs. And US producers are selling growing volumes to Canadian buyers.

The overarching objective of this paper is to consider whether there is any evidence of a shift in perception in the United States of the role of Canadian production as a source of US natural gas supply. This section has highlighted the existence of two distinct periods in the patterns of natural gas production in Canada and the United States, and in trade flows between these two countries. The question of interest to us now is whether these changing activity patterns have led to reassessments of the long-term place occupied by Canadian natural gas in US markets. We turn to this task in the next section.

The Place of Natural Gas from Canada in the United States: An Assessment of EIA Projections

Every year, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) produces an Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) that provides an overview of and commentary on expected future developments in US energy markets, including some of major trade patterns of relevance to the United States. Each edition of the AEO includes, among other things, long-term projections of key measures of production, consumption, and trade by energy source. US natural gas imports from and exports to Canada are both explicitly included as separate variables in these projections.

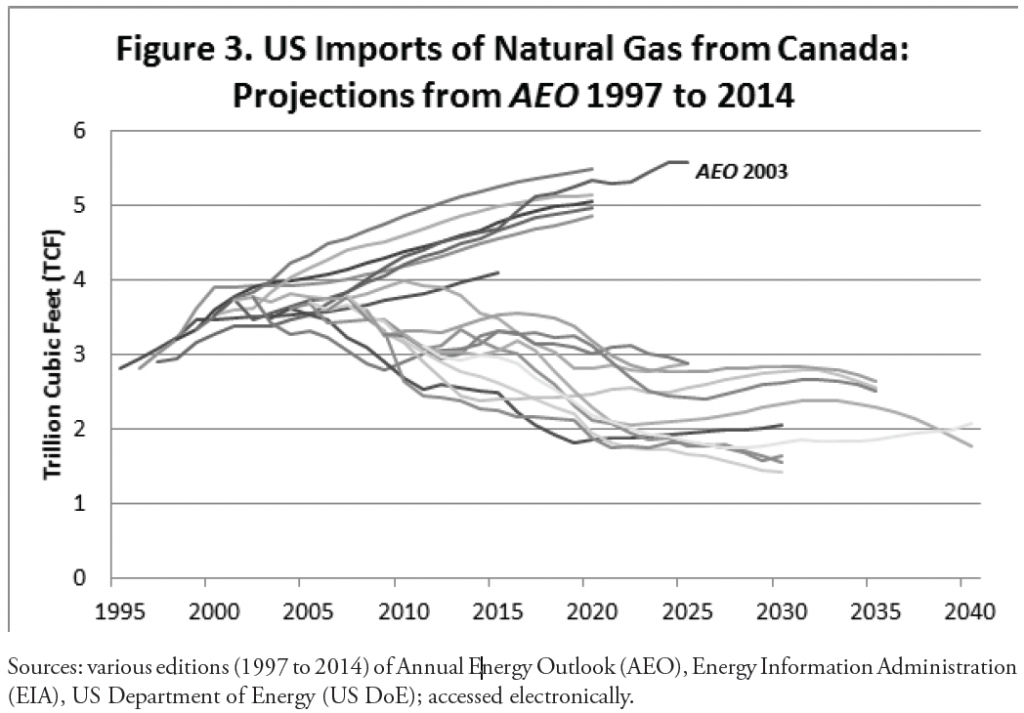

The EIA website contains detailed information about the long-term projections included in every edition of the AEO for the period 1997 to 2014. The “reference case” values of the projected series for US imports from Canada and for exports of US-produced natural gas to Canada were collected from the 18 editions of the AEO issued during the period identified above. To give the reader an impression of the information thereby assembled, Figure 3 provides a representation of the projections of US natural gas imports from Canada contained in each of the AEO editions included. For ease of presentation, only the projection from AEO 2003 is labelled in Figure 3, which allows, in turn, the use of that specific projection to describe what each of the series represents.

The series extracted from AEO 2003 contains values for each year extending from 2001 to 2025. The entries for the first two years (2001 and 2002) are the import volumes either observed or estimated for these two years. Projected values for the years 2003 to 2025 complete the series. Each individual projection (i.e., each “line” in Figure 3) is constructed in the same manner: actual “data” for the first few years and then projected values for all of the remaining years to the end of the period considered in the specific AEO edition from which the given series is taken.

Figure 4 illustrates the first important change in the view of the role of Canadian natural gas in the United States that emerges from the AEO projections. From 1997 to 2001, the projection included in each annual edition of the AEO called for rising gas imports from Canada over the time period considered. The 1997 projection, represented by the short “dash-dot” line in Figure 4, establishes this pattern. Each subsequent projection until that in 2001 (for ease of presentation, the only one of these shown in Figure 4) incorporate rising imports over the time period of the projection, and also calls for progressively larger volumes of imports in any given year of the projection period. Were these to have been included in Figure 4, the projections for the 1998, 1999, and 2000 editions of the AEO would lie between that from the 1997 edition and the one from 2001 (the dashed line at the top of Figure 4). According to AEO 2001, (net) US natural gas imports from Canada were to reach 5.5 TCF in 2020 and account for 16.7 per cent of domestic consumption in that year.6 What is not evident from Figure 4 is that almost all US imports of natural gas are sourced in Canada in the projections incorporated in the AEO editions issued between 1997 and 2001.

As highlighted in the previous section, the period from 1997 to 2001 witnessed sustained growth in Canadian natural gas production and rising export volumes to the United States. The AEO editions produced during this time period thus translate this situation into a representation of Canada as an everlasting (at least until the end of the projection period) secure and reliable source of US gas imports. In AEO 2001, reference is made to additional imports coming from Western Canada and to production from Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia, reaching US consumption markets as of the beginning of 2000. Mexico is seen as a destination for small volumes of US gas exports, while liquefied natural gas (LNG) is seen as growing in importance over time, but “is not expected to grow beyond a regionally significant source of U.S. supply…”7 Until 2001, the “story” of US natural gas imports in the AEO projections remains essentially told by exports from Canada.

Things begin to change in 2002. The US supply picture improves in the 2002 edition of the AEO and the growing importance, especially in the projection period, of “tight sands, shale, and coal bed methane” as sources of US natural gas supply is specifically highlighted. This is accompanied by a slightly more expansive view of the role of LNG in meeting future US consumption needs.8 These two factors – but principally the more optimistic view of US gas production potential – overlay a situation where imports from Canada decline slightly in importance in the overall representation of developments on US natural gas markets, as the solid line in Figure 4 indicates.

The 2003 projection (the dashed line extending to 2025 in Figure 4) brings a few additional factors into consideration. Here, the unconventional sources of production identified above continue to play an increasingly important role in the overall natural gas supply picture in the United States, but AEO 2003 is much less optimistic about the prospects for post-2015 conventional production in the lower 48 states than had been the case one year earlier. The projected decrease in overall US production that results is assumed to be met by increased imports from Canada and by growing LNG imports.9 As represented in AEO 2003, Canada remains an important part of the supply picture of natural gas in the United States, but this position seems increasingly challenged by US unconventional production and by imports in the form of LNG.

The representation of the place of Canadian natural gas in the Unites States changes dramatically in AEO 2004, as Figure 4 shows. This is not driven by changes in the perception of the role to be played by US domestic production. Instead, the picture presented in AEO 2004 is one of decreasing production capacity in Canada, especially in the Western Sedimentary Basin, and of the absence of significant new discoveries offshore Canada’s East Coast. Imports from Canada are projected to peak in 2010 and then to decrease gradually to 2025 and the end of the projection period, this despite the continued inclusion in the projection of a Mackenzie Valley pipeline, assumed to bring volumes of natural gas from Canada’s North to US markets beginning in 2009. In other words, there has been a downward reassessment of Canada’s overall potential as a source of natural gas supply for US consumers and, as far as the authors of AEO 2004 are concerned, LNG imports from other countries will step into the breach, with volumes projected to rise from 0.2 TCF in 2002, to 4.8 TCF in 2025.10 AEO 2005 takes this change in perception of Canada as a source of natural gas for the United States further: imports of Canadian-produced gas are seen as having peaked in 2003, prior to the beginning of the projection period (dotted line extending to 2025 in Figure 4). LNG imports, on the other hand, are projected to ramp up faster and to reach higher levels by the end of the forecast period: imports of 6.4 TCF in 2025, compared to a projection of 4.8 TCF put forward only one year earlier in AEO 2004.11

As noted in the previous section, Canadian natural gas production plateaued and US production fell slightly between 2002 and 2007. Within a few years of the beginning of this period, the projections incorporated into the AEO editions reflected this changing reality of natural gas production in the two countries. This resulted in a reassessment of the role that Canadian-produced gas was expected to play in the US marketplace: imports from Canada were no longer seen as being sufficiently large to close the gap between US consumption and production. The remaining gap would be closed by LNG imports, which eventually acquired a much greater importance in meeting US consumption in AEO projections. This is most starkly revealed by a comparison of the projection in AEO 2003 and that in AEO 2004. In the course of a single year, the assessment of future Canadian natural gas production capacity included in AEO projections worsened significantly and LNG imports were expected to begin to play part of the role that had thus far been reserved to production from Canada in projections of US natural gas supply-demand balances.

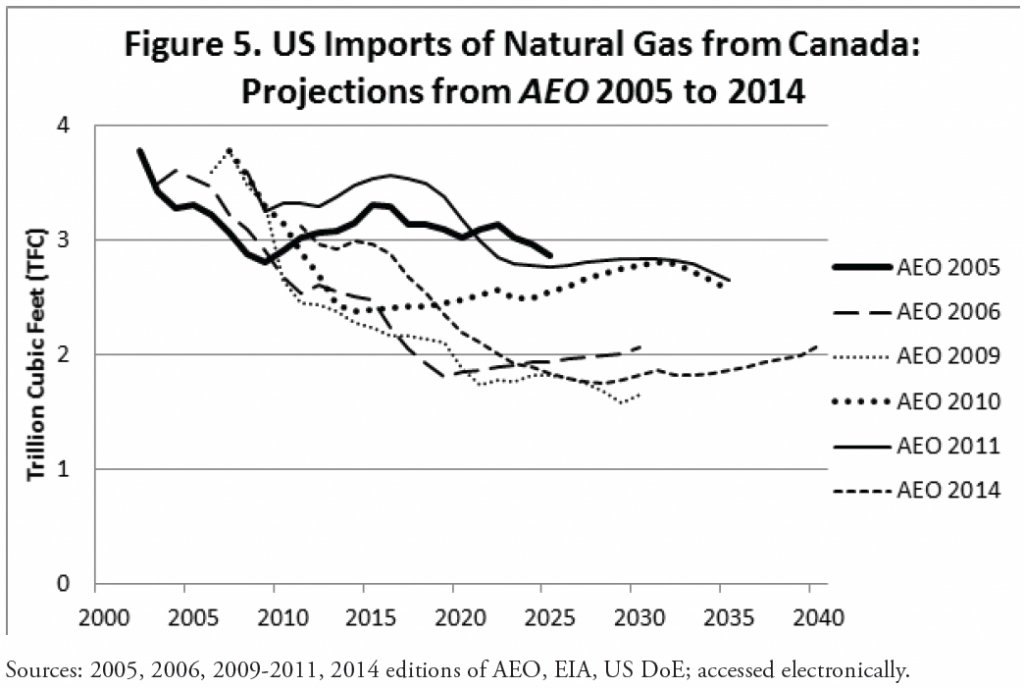

The next transitions in the views expressed in the AEO about the prospective role of Canadian-produced in the United States are less starkly defined, though no less important, than the one described above. Figure 5 shows projections from a number of AEO editions issued between 2005 and 2014. These specific projections were selected to document the changes in perspective that occurred, while facilitating presentation (and allowing for Figure 5 to be relatively easy to interpret).

Our starting point is the last projection included in Figure 4, namely that from AEO 2005 (now the short, thick line in Figure 5). In the course of the next four years, successive AEO editions featured projections that incorporated a trend of decreasing US reliance on imports of natural gas from Canada. Basically, the entire projected time profile of imports (except for the first few years of the projection period) drifted downward year after year, eventually reaching that included in AEO 2009 and represented by the dotted line extending to 2030 in Figure 5. Three key factors sustain these changing views. First, successive projections present an increasingly optimistic view of US production: from an expected decline over the projection period in AEO 2006, to a long-term flat production profile in AEO 2007, to one characterized by modest growth (AEO 2008), and then solid growth (AEO 2009). All of these changes are directly linked to an upward revision in the potential of the unconventional (and especially shale) resource base in the United States.

Second, whenever higher import volumes are needed to close the projected gap between US natural gas production and consumption, LNG is assumed to play that role. Sharp increases in LNG imports, typically beginning a few years into the projection period, characterize the projections in successive AEO editions issued during most of this period. In AEO 2008, for example, LNG imports into the United States are projected to be twice the size of the imported volumes of Canadian-produced natural gas: 2.8 vs 1.4 TCF, respectively, in 2030.12 There is also an interaction between the two factors identified above. The marked increase in expected US production incorporated into AEO 2009 is accompanied by a downward re-assessment of the role of LNG in meeting future US natural gas demand: projected LNG imports in 2030 are now below 0.9 TCF,13 less than one-third the level projected only one year earlier in AEO 2008. Faster growth in US production is expected to displace increasingly large volumes of imported LNG.

A third factor that underlies this picture of a growing US natural gas self-reliance is the projected evolution of Canadian natural gas production and its disposition. Canada’s production capacity from conventional sources – mainly the Western Sedimentary Basin – is seen by the AEO authors as being in a situation of long-term decline. Growth prospects for Canada’s Arctic region and from unconventional sources are projected to be too modest for production from these sources to offset fully the expected decline in conventional production. To make matters worse, the Mackenzie Valley pipeline that had been featured in the AEO for many years was taken out of the projection in AEO 2008: construction of the pipeline was assumed to be pushed back beyond the end of the projection period (a situation that has continued to prevail in subsequent editions of the AEO, including the most recent one).14 AEO 2009 includes a more optimistic view of Canada’s production potential from unconventional sources, but now domestic demand patterns are seen as curbing the country’s export potential: “…Canada’s unconventional production does not increase rapidly enough to keep up with domestic demand growth while maintaining current export levels.”15 As the dotted line extending to 2030 in Figure 5 reminds us, even though the assumed prospects for LNG imports into the United States dimmed considerably from AEO 2008 to AEO 2009, this was not sufficient to bring about a meaningful re-appraisal of the overall role of Canadian-produced natural gas in the US marketplace. Instead, increased US production is projected to make up for any decrease in LNG import volumes.

In AEO 2010, shale gas is presented as “…the largest contributor to the growth in [US] production.”16 Despite this buoyant portrayal of future production prospects in the United States, imports from Canada were projected to rebound somewhat in comparison to the picture presented in AEO 2009. As the dotted line extending to 2035 in Figure 5 indicates, the expected increase in import volumes from Canada is particularly noticeable after 2020. What is not obvious from Figure 5 is that this increase was accompanied by a corresponding fall in projected LNG imports. In the longer term, therefore, AEO 2010 still portrays Canadian production as an important source of supply from which to meet changes in the long-term prospects for US LNG trade.

The first few years of the projection period in AEO 2011 are characterized by an upward “blip” in import volumes from Canada (see the solid line extending to 2035 in Figure 5). The accompanying text reveals that the AEO authors see these higher volumes as being linked to stronger expected US consumption and improved short-term production prospects from unconventional sources in Canada. As the projection horizon is extended, however, Canadian imports are assumed to return to the levels characteristic of AEO 2009.

From then on, successive editions of the AEO depict Canadian-produced natural gas as playing a smaller and smaller role in meeting US demand: the entire profile of projected US imports of natural gas from Canada drifts downward, eventually reaching in AEO 2014 that represented by the dashed line extending to 2040 in Figure 5. LNG imports don’t fare any better: these fall even further in the AEO 2011 projection and effectively disappear in AEO 2012. In contrast, US production is portrayed as characterized by strong growth, both from one AEO edition to another (i.e., upward shifts of the projected production profile) and within each individual projection (i.e., production growing over time). The key driver of these improved prospects is the strong, sustained growth projected for US shale gas production. Indeed, in AEO 2012, the United States is portrayed as a net exporter of natural gas, beginning in 2020. Subsequent AEO editions have painted an even more aggressive picture of the supply-demand balance for natural gas in the United States: in AEO 2014, net exporter status is projected to be achieved in 2018 and (net) LNG exports reach 3.5 TCF by 2030.17 This, of course, marks a dramatic reversal in the perceived place of LNG in US natural gas trade from that projected to occur as recently as in AEO 2008.

Perhaps the most telling description of the “new” perceived role of Canadian-produced natural gas in the United States can be found in AEO 2013: “[e]ven as overall consumption exceeds supply in the United States, some natural gas imports from Canada continue, based on regional supply and demand conditions”[emphasis added].18 The reader will recall that, as noted earlier, quite similar words were used in AEO 2001 to describe the projected role of LNG imports in the overall picture of natural gas in the United States.

In AEO 2014, imports from Canada are expected to account for approximately 7.2 per cent of US natural gas consumption in AEO 2014 by the end of the projection period in 2040, namely 2.07 of 28.45 TCF.19 Since this arguably still represents a reasonably large proportion of US natural gas use, in what sense can it be seen to indicate a limited role (“based on regional supply and demand conditions”) for Canadian-produced natural gas in the United States? Figure 6 sheds some light on this matter. The two lines at the top left of that Figure represent the projections from AEO 2003 for gross and net US imports of natural gas from Canada, where net US imports are defined as gross US imports from Canada minus gross US exports to Canada. The two lines at the bottom right of the Figure represent the same concepts, with projected values taken from the 2014 edition of the AEO. A key difference should now be clear: projections of the size of US export volumes to Canada (and mainly to Eastern Canada) have increased markedly in the eleven years that separate these two AEO editions. In all editions of the AEO issued between 1997 and 2003, projected US exports of natural gas to Canada are essentially negligible. With AEO 2004, however, the expectations are for volumes of natural gas exported from the United States to Canada to grow, both within a given projection period and across AEO editions – a trend that becomes increasingly pronounced as the release date of individual AEOs get closer to the present day.

In the projections incorporated into AEO 2003, never do US exports to Canada reach 0.3 TCF and never do these exceed 6.25 per cent of the volumes of natural gas expected to flow in the opposite direction.20 As far as AEO 2014 is concerned, however, US export volumes to Canada are expected to vary between 0.99 and 1.45 TCF over the projection period.21 In relative terms, this means that US export volumes to Canada never fall below 33 per cent of the volumes of natural gas projected to be imported into the United States from Canada, and this proportion exceeds 65 per cent (or ten times the highest value observed in the AEO 2003 projection) in more than one-half of the years in the projection period. As Figure 6 shows, net imports from Canada are thus not expected to exceed 0.9 TCF between 2022 and 2040. Indeed, the AEO 2014 projection for net US imports of natural gas from Canada in 2040 (the last year of the projection period) is 0.71 TCF, or 2.5 per cent of US consumption in that year.22 In this context, Canadian-produced natural gas can indeed be characterized as playing a limited role in the US marketplace, one that is quite likely focused on a few specific regions of that country.

Reflections on Implications for Canada and for North American Gas Markets

The picture of the future North American natural gas market that emerges from these successive EIA projections is one of a continued integrated Canada-US marketplace, but one where the nature of the integration changes from an almost exclusively one-way flow of production from Canada to the United States, to one of rising (net) Canadian imports of US-produced natural gas. It seems reasonable to conclude that in and of itself this change should not affect natural gas pricing dynamics in the two countries. If this were to be the only change to be considered then production from shale and tight sands formations in Canada would continue to respond to made-in-North-America natural gas prices.

But what about the potential for significant volumes of LNG exports identified in the EIA projections and resulting from proposed export projects in Canada (especially British Columbia)? The expected destinations for these export volumes are mainly consumption markets in Asia, where delivered prices of natural gas have tended to exceed – sometimes by wide margins – those in North America. In 2013, for example, delivered prices of natural gas in Japan averaged $(US) 16.17 per million BTU, while the average price at Henry Hub equaled $(US) 3.71.23 Even if the volumes consumed are much smaller than in North America,24 it seems clear that North American natural gas production destined for export markets in Asia would put upward pressure on prices in North America, at least in the short to medium term, irrespective of whether the LNG exports were from Canada or the United States. The commercial logic of these prospective higher prices no doubt fuels, at least in part, current proposals for LNG export projects in these two countries.

A critical issue then becomes the extent of price arbitrage that could be expected to occur if these two previously disconnected natural gas “islands” (Asia and North America) begin to experience some degree of market integration through LNG trade. At the outset, it should be clear that the extent of upward price pressure in North America would depend on the price responsiveness of demand in target export markets. The less price responsive (i.e., the more inelastic) the demand for natural gas in these markets, the less intense will be the pressure for upward price movement in North America. In such a case, one would expect this pressure to be largely dissipated as a result of price decreases in the target export markets, all else held equal.

An additional complication relates to the role of liquefaction capacity in the exporting countries. To the extent that this capacity is scarce relative to the LNG export market potential, the higher delivered prices in Asia are likely to result, at least for some time, in opportunities for higher-than-normal returns on liquefaction capacity investments as opposed to higher natural gas prices in North America. This creates policy and regulatory challenges in Canada and the United States in terms of whether and how to address the possibility of higher-than-normal returns on energy infrastructure investments. More generally, the extent of liquefaction capacity constraints (or, equivalently, of constraints on LNG shipping capacity) and its evolution over time will clearly affect the extent and intensity of upward pressure on natural gas prices in North America, which in turn will play a role determining the prospects for the development of unconventional natural gas deposits in Canada.

The emergence of a more balanced natural gas trade pattern between Canada and the United States provides an interesting vantage point from which to consider some proposed Canadian energy infrastructure projects, especially LNG export terminals in British Columbia and Energy East, the conversion (and extension) by TransCanada of one of its West-to-East natural gas pipelines into an oil line. Broadly speaking, natural gas production in British Columbia (or Western Canada, more generally) from newly developed (and mostly unconventional) reserves could potentially reach two distinct markets: Asia and Eastern Canada. The first of these opportunities is what motivates the proposals for LNG export terminals located on Canada’s West Coast. As noted earlier, delivered prices in Asia are much higher than in North America, and so there is an incentive, at least in the short to medium term, to attempt to translate these higher prices in Asia into positive returns on energy investments in Canada.

A second option would be to use the existing inter-provincial pipeline infrastructure (and any required additions thereto) to enable BC-produced natural gas to displace, mostly in Eastern Canada, projected volumes of imports from the United States. The Energy East project then comes to the fore: how would the conversion of a natural gas transmission pipeline to other purposes affect the business case for deliveries to Eastern Canada of natural gas produced in British Columbia? To the extent that the existing infrastructure (minus the line at the heart of Energy East) could accommodate the incremental volumes without any capacity constraints, then the proposed conversion could be expected to have little to no effect on the business case for shipments of BC-produced gas to Eastern Canada. The situation would be different, of course, if the proposed conversion led to the creation of natural gas transmission capacity constraints in Canada. The regulatory process assessing the proposed pipeline conversion would arguably be an appropriate venue in which to consider this issue.

Overall, Canadian sellers and shippers will need to choose how to dispose of this new production. The existing policy approach in Canada of reliance on market forces would give rise to a situation where buyers, sellers and shippers of this new production would assess the risks and the potential benefits and costs of alternative courses of action, and through their actions determine if one, the other, or both of the options identified above are worthwhile paths to follow. With this kind of approach, regulatory intervention would only be used to address specific issues that would impede market operations, such as the potential creation of transformation and transportation capacity bottlenecks. To the extent that policy-makers were to elect, as a matter of policy, to favour one option over another, they run the risk that such action will lead to a lower realized value of the natural gas reserves whose development, production, and disposition are linked to the market opportunities considered in the last few paragraphs.

Overview and Summary

An assessment of specific aspects of comprehensive projections of the evolution of US natural gas markets produced by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), an agency of the US Department of Energy led to the identification of marked changes in the role of Canadian-produced natural gas in the United States, as reported in the editions of the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) released between 1997 and 2014.

There was a sharp break in the perceptions of the role expected to be played by US imports of natural gas from Canada between the 2003 edition of the AEO and that issued in 2004. Successive AEO editions released between 1997 and 2003 each incorporated an expectation of a growing role for Canadian-produced natural gas over the course of the projection period and of an expanded presence in the US marketplace across projections. Not only did AEO 2004 incorporate a sharp downward shift in the time path of projected gas imports from Canada, but it was also characterized by a change in the “slope” of this time path: no longer were imports from Canada perceived as growing over time; rather, import volumes were expected to fall as the projection horizon lengthened. Changes in the anticipated long-term productive capacity of the Canadian resource base were at the heart of this re-assessment. And, as the review of key activity measures undertaken earlier in the paper indicates, the timing of this re-assessment corresponds closely to a change in the pattern of natural gas production in Canada: from a period of sustained growth, to one where output plateaued.

This change in the perceived role of Canadian-produced gas in the US marketplace was reinforced in subsequent AEO editions, at the same time as actual Canadian natural gas production began to fall. Basically, a sustained downward drift in the projected time path of US imports of natural gas from Canada was incorporated into issues of the AEO released between 2005 and 2014. There was a re-assessment of the perceived role of Canadian gas in the United States in AEO 2010 and 2011, where slight upward shifts in the projected time path of US imports from Canada were observed. But this re-assessment proved short-lived and the downward drift of the time path of projected imports began again in AEO 2012. Initially, sharp increases in LNG imports were expected to compensate for the falling natural gas volumes projected to be imported from Canada. Eventually, however, sustained pronounced increases in the production of shale gas in the United States were expected to reduce sharply the need to draw from foreign sources of natural gas to meet US consumption needs.

In the 2014 edition of the AEO, these increases in US shale gas production are expected to be strong enough to transform the United States into a net exporter of natural gas before 2020. It is perhaps not surprising then that the re-assessment of the role of Canadian gas is even more starkly defined when both directions of natural gas trade flows between the two countries are considered, and net US imports are tracked. By the end of the projection period in 2040, (Eastern) Canada becomes a destination for US exports of natural gas and net US imports from Canada amount to less than 2.5 per cent of total projected US consumption. Canada’s role is perceived as that of a player on some regional markets in the United States, in sharp contrast to the situation that prevailed in editions of the AEO issued in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The “glory days” of Canadian-produced natural gas in the US marketplace thus appear to be behind us, never to return (at least, not to return before well after 2040!), if the projections incorporated into recent AEO editions are to be believed.

Since projected increases in US production are expected to lead to significant export volumes via pipeline to Canada and in the form of LNG to more distant (especially Asian) markets, possible implications of these developments were also examined. The potential for natural gas price increases in North America in the short to medium term was seen as conditional on a number of other factors, including liquefaction capacity constraints in Canada and the United States. An assessment of recent EIA projections suggests that production from newly tapped natural gas deposits in Western Canada could result not only in LNG exports from British Columbia, but also in the displacement of some volumes of US-produced gas that would otherwise be imported into Eastern Canada. To the extent that policy intervention or the design of the relevant regulatory regime expressly favours one over the other of these two options, then a possible consequence is a reduction in the realized value of these newly tapped natural gas deposits. Transmission capacity constraints could also affect the business case for pipeline transmission from British Columbia to Eastern Canada. It would seem appropriate to consider these factors and their possible implications in the regulatory process dealing with TransCanada’s proposed Energy East project.

In the end, a changing role for Canadian natural gas on US markets may well create opportunities for Canadian producers (and consumers) to explore new possibilities for the disposition of higher domestic production volumes that may be realized in the future. An assessment of the expected place of Canadian gas in the United States has led to reflections on new market opportunities outside of that country.

- André Plourde is Professor, Department of Economics and Dean, Faculty of Public Affairs at Carleton University. Thank you to Joti Randhawa for research assistance.

- For early discussions of the deregulation process directed at Canada’s natural gas industry, see chapter 4 of John F. Helliwell et al, Oil and Gas in Canada: The Effects of Domestic Policies and World Events (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1989) and National Energy Board (NEB), Natural Gas Market Assessment (Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada, October 1988). For a ten-year assessment, see NEB, Natural Gas Market Assessment – Ten Years after Deregulation (Calgary: National Energy Board, November 1996).

- The production measure used here is deliveries of marketable gas. The primary source for both Canadian production and export data is Statistics Canada.

- US natural gas data used in this paper were obtained from the website maintained by the US Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration.

- Note that in this paper when the term “imports” is used on its own, it is taken to mean “gross imports”. The same applies to “exports”.

- Sources for these projected values are Energy Information Administration (EIA) Supplement Tables to the AEO 2001 (accessed electronically) at Table 82 and Annual Energy Outlook 2001, With Projections to 2020 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, December 2000) at 83, respectively.

- Ibid.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2002, With Projections to 2020 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, December 2001) at 82.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2003, With Projections to 2025 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, January 2003) at 76.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2004, With Projections to 2025 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, January 2004) at 91.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2005, With Projections to 2025 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, February 2005) at 96.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2008, With Projections to 2030 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, June 2008) at 78 [AEO 2008] for LNG imports; EIA, Supplemental Tables to the Annual Energy Outlook 2008 (accessed electronically) at Table 106 for imports from Canada.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2009, With Projections to 2030 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy: March 2009) at 78 [AEO 2009].

- AEO 2008, supra note 12.

- AEO 2009, supra note 13.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2010, With Projections to 2035 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, May 2010) at 72.

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2014, With Projections to 2040 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, April 2014) at MT-22, Table 134 [AEO 2014].

- EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2013, With Projections to 2040 (Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, April 2013) at 79.

- AEO 2014, supra note 17, Table 134 for imports from Canada and Table 135 for US consumption.

- EIA, Supplement Tables to the Annual Energy Outlook 2003 (accessed electronically) at Table 104.

- AEO 2014, supra note 17.

- Ibid.

- This price information is from BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2014 (London, UK: British Petroleum, June 2014) at 23, online: BP <http://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/Energy-economics/statistical-review-2014/BP-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2014-full-report.pdf>.

- For example, according to ibid at 27, total consumption of natural gas in Canada and the United States reached 29.7 TCF in 2013. Comparable values for Japan and South Korea – key existing target markets – were 4.1 and 1.9 TCF, respectively; at 5.7 TCF, total consumption in China was slightly smaller than that in Japan and South Korea combined. Consumption in these three countries combined was slightly less than 40% of the Canada-US total in 2013.