INTRODUCTION

On April 6, 2022, the federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change announced his decision that the proposed Bay du Nord oil development project (BdN Project), located offshore in the Flemish Pass Basin approximately 500 kilometres east of St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, “is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects when mitigation measures are taken into account.”[1] The Minister’s decision, with 137 conditions, clears the path for the project to proceed through several remaining regulatory steps.

The announcement had been delayed twice, adding to anxiety among interested parties that the project might be rejected. It had been reported that there was opposition within the federal cabinet to approving the project.[2]

Not surprisingly, the decision was heavily criticized by advocates for stronger measures to restrict carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions,[3] particularly coming as it did only a week after the release of the federal government’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan: Canada’s Next Steps for Clean Air and a Strong Economy.[4] At the same time, the government of Newfoundland and Labrador welcomed the announcement, with the Premier reportedly describing it as a “giant step forward” for the project and a key part of an economic recovery for the provincial government.[5] Industry reportedly described the approval as a “triumph”.[6] The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) issued a statement it was “pleased that the Government of Canada relied on the science”.[7]

Reservations about the future prospects for new oil and gas development projects are widespread, both in Canada and internationally. Only a year ago, the International Energy Agency (IEA) issued a report stating that no new oil and gas fields should be approved for development if the world is to meet its climate goals and limit global warming.[8] The Minister’s decision is a significant milestone indicating that, notwithstanding the IEA’s report, a path forward remains for such developments in Canada, challenging as that path might be.[9]

In this regard, the conditions attached to the decision are particularly significant; for the first time, they include a legally binding requirement that a project proponent achieve net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050.

From a broad regulatory perspective, the decision is of fundamental, systemic significance. In particular, it confirmed that, at least since the enactment of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012,[10] the threshold determination of whether a resource development project that invokes federal jurisdiction will be allowed to proceed is unequivocally to be made by the responsible Minister (or in some circumstances by the Governor in Council), which is to say at the political level.

It might also be asked whether that reality — that a federal minister unilaterally makes the “go/no go” decision on the BdN Project and presumably any future projects offshore from Newfoundland and Labrador — erodes the principle of joint federal-provincial management underlying the Atlantic Accord.[11]

The decision also places the BdN Project a step closer to being the first offshore oil and gas project in the world to trigger Article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[12] As is discussed briefly below, Article 82 would oblige Canada to make payments to the international community based on production from the BdN Project.

The Minister’s decision is an important milestone in advancing the BdN Project. It must be noted, however, that no decision has yet been made to proceed with development.

THE BAY DU NORD PROJECT

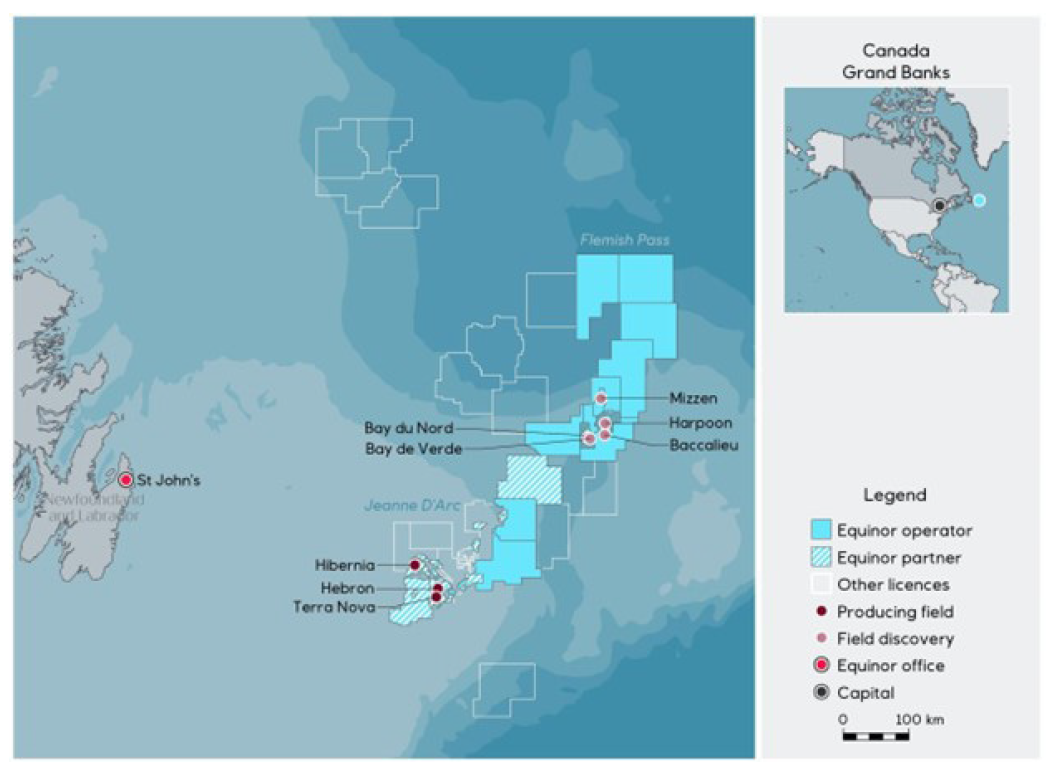

The BdN Project is a proposal by Equinor Canada Ltd. (Equinor)[13] to develop two significant oil discoveries, Bay du Nord and Baccalieu (discovered in 2013 and 2016 respectively), with a view to commencing production in the late 2020s using a floating production, storage and offloading vessel (FPSO).[14] Rights to the two discoveries are currently held under significant discovery licences issued by the Canada-Newfoundland & Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board (C-NLOPB) to Equinor and Cenovus Energy Inc. (as successor to Husky Oil Operations Limited). Rights to adjacent discoveries drilled in 2020 that could potentially be tied into the project are held by Equinor and BP Canada Energy Group ULC. Further exploratory drilling in the area is planned for 2022. Any resulting discoveries would be considered for potential tie-ins to the BdN Project.

Equinor estimates the recoverable reserves of the BdN Project to be approximately 300 million barrels. Production is expected to approach 200,000 barrels per day. Project cost is estimated to be $CAN12 billion. Equinor estimates revenues to government will be $3.5 billion over the project’s anticipated lifespan of 30 years.

Source: Equinor website: https://www.equinor.com/en/where-we-are/canada-bay-du-nord.html. Reproduced with permission.

THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

The primary regulatory agency with direct authority over oil and gas activities offshore from Newfoundland and Labrador is the joint federal-provincial C-NLOPB, established by legislation enacted by each of Parliament[15] and the provincial legislature[16] to implement the Atlantic Accord.[17] However, the BdN Project also comes under the CEA Act, 2012 as a designated activity.[18] A Memorandum of Understanding between the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (Agency) and the C-NLOPB, dated February 20, 2019, provided that an integrated environmental assessment and regulatory review of the BdN Project would be undertaken.[19]

On August 9, 2018, the Agency determined that an environmental assessment was required under the CEA Act, 2012. While the CEA Act, 2012 was repealed on August 28, 2019, by the Impact Assessment Act,[20] the effect of the transitional provisions of the later Act was that the environmental assessment of the BdN Project continued under the CEA Act, 2012 as though that Act had not been repealed. The Agency therefore proceeded to conduct an environmental assessment of the BdN Project in accordance with section 5 of the CEA Act, 2012.

The Agency’s Environmental Assessment Report (EA Report)[21], dated December 2021 but not released until April 2022, was prepared in consultation with the C-NLOPB, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Health Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Transport Canada, Parks Canada Agency and the Department of National Defence. The views of Indigenous peoples and the general public were also considered.[22]

The EA Report concluded that the BdN Project “is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects, taking into account the implementation of the mitigation measures described in this EA Report.”[23] It identified “key mitigation measures and follow-up program requirements for consideration by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change (Minister) in establishing conditions as part of the decision statement in the event that the Project is permitted to proceed.”[24]

Having received the EA Report, the Minister was obligated to then decide if “taking into account the implementation of any mitigation measures [the Minister] considers appropriate [the BdN Project] is likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects”, within the meaning of specific sections of the CEA Act, 2012.[25] The Minister must then establish “the conditions in relation to the environmental effects…with which the proponent of the…project must comply.”[26] Further, the Minister must issue “a decision statement” (Decision Statement) informing the proponent of the decisions made and including the conditions.[27]

WHO DECIDES?

Before proceeding to discuss the Minister’s Decision Statement, the central structural feature of this regulatory scheme should be noted. Firstly, when making the mandated decisions with respect to the likelihood of significant adverse environmental effects, the Minister (or in certain circumstances the Governor in Council) is only obligated to “take into account” the report of the Agency. The scheme is silent on whether the Minister may take into account other considerations. Similarly, it is the Minister who “must establish the conditions” with which a project proponent must comply.

As noted, the CEA Act, 2012 under which the BdN Project was assessed has been repealed. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the assessment process established under the successor Impact Assessment Act[28], which came into force on August 28, 2019. However, for present purposes it is noted that the architecture of the assessment processes is broadly similar under both Acts and that the Minister is similarly obligated under the later Act to make a determination only after “taking into account”[29] an assessment report and to “establish any condition that he or she considers appropriate…with which the proponent…must comply.”[30] The Impact Assessment Act expressly states that the Minister’s determination “must be based on the report…and a consideration of” certain specified factors, including the extent to which the project contributes to sustainability and the extent to which the effects of the project “hinder or contribute to the Government of Canada’s ability to meet its environmental obligations and its commitments in respect of climate change.”[31]

It is clear under both the CEA Act, 2012 and the Impact Assessment Act, that the “go/no go” decision (including conditions) on projects that are subject to either Act is consolidated at the political level, to be made unilaterally by the responsible Minister (or in certain circumstances by the Governor in Council[32]). It is noted, however, that there is a lack of transparency with respect to the process followed by the Minister, in making the mandated decision (including the attachment of conditions) after having received the Agency’s Assessment Report.

The BdN Project review process can thus be seen as another illustration of what appears to be a broader trend to remove decision-making authority with respect to the review of energy development projects from the mandates of independent regulatory agencies and consolidate that authority in the hands of elected officials.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE ATLANTIC ACCORD

The Atlantic Accord is a 1985 agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador providing for the “joint management of the offshore oil and gas resources off Newfoundland and Labrador…”[33] The enumerated purposes include:

…to recognize the equality of both governments in the management of the resource, and ensure that the pace and manner of development optimize the social and economic benefits to Canada as a whole and to Newfoundland and Labrador in particular…[34]

A unilateral threshold decision by the federal government on whether a project will or will not be allowed to proceed appears to be inconsistent with the concepts of “joint management” or “equality of both governments in the management of the resource”.

There have not been any reports of the issue having been raised during the review process for the BdN Project. Given the provincial government’s enthusiastic support of the project, however, it can be speculated that the issue might well have led to a full-blown federal-provincial dispute had the Minister’s decision been otherwise.

The approval of the BdN Project may, however, have only brought a temporary reprieve. In the wake of the release of the Decision Statement, it was reported that the Minister had hinted the BdN Project could be the last such project.[35] The provincial government, on the other hand, expects the offshore oil and gas industry to continue to grow.[36] Future tensions between Ottawa and St. John’s, may, therefore, be expected.

MINISTER’S DECISION STATEMENT

The central determination recorded in the Minister’s Decision Statement[37], released on April 6, 2022, is the conclusion that, “after considering the report of the Agency on the Designated Project and the implementation of mitigation measures that I consider appropriate [the BdN Project] “is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects…”[38] The Decision Statement also records 137 “legally-binding conditions.”[39]

As noted, the Assessment Report was prepared by the Agency in consultation with other agencies, Indigenous peoples and the public. Of particular relevance, these included agencies with direct responsibilities engaged by the BdN Project, namely the C-NLOPB (under the Accord Acts[40]) and the Minister of Fisheries (under the Fisheries Act[41] and the Species at Risk Act[42]). As was to be expected therefore, the conditions set out in the Minister’s Decision Statement cover a wide and varied range. Many would not be unusual as applied to an offshore oil development project such as BdN.

One particular group of these conditions, however, is noteworthy for focusing directly on requirements to reduce GHGs from the BdN Project and, for the first time ever,[43] requiring a proponent to achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.

GHG EMISSIONS

Condition 6.2 requires the proponent to identify and incorporate GHG emission reduction measures into the design of the BdN Project and implement these measures for its duration. In doing so, the proponent is required to take into account “the most recent guidance issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada related to greenhouse gas mitigation measures and the quantification of net greenhouse gas emissions.”

Condition 6.4 provides:

Commencing on January 1, 2050, the Proponent shall ensure that the Designated Project does not emit greater than 0 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per year (kt CO2 eq/year), as calculated in equation 1 (section 3.1) of Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Strategic Assessment of Climate Change and any associated guidance documents published by the Government of Canada.

The News Release accompanying the Minister’s Decision Statement cited the BdN Project as “an example of how Canada can chart a path forward on producing energy at the lowest possible emissions intensity while looking to a net-zero future.”[44] While the Release noted that emissions from the project would be “five times less emissions intensive than the average Canadian oil and gas project, and ten times less than the average project in the oil sands”, it was silent on the actual volume of GHGs (acknowledged to be less intensive) that would be emitted by the BdN Project.

ARTICLE 82 OF UNCLOS

As noted, no decision to proceed with the BdN Project has been made. The Minister’s Decision Statement is, however, an important milestone towards that end and advances the possibility that the project could become the first in the world to trigger a coastal state’s obligation under Article 82 of UNCLOS[45] to make payments to the international community based on production. As discussed in a previous issue of Energy Regulation Quarterly[46], Article 82 of UNCLOS requires the coastal state to make payments or contributions in kind in respect of the production of non-living resources beyond 200 nautical miles. Such payments must be made annually, commencing at 1 per cent in the 6th year of production and increasing by 1 per cent per year until the 12th year. Thereafter, the payments or contributions remain at 7 per cent. Payments or contributions are to be made through[47] the International Seabed Authority to states parties to UNCLOS “on the basis of equitable sharing criteria…”[48] To date, Canada has not adopted any mechanism to actualize its obligation under Article 82 and it is an open question who within Canada would ultimately bear the cost of these payments.[49]

CONCLUSIONS

The Minister’s Decision Statement has cleared the BdN Project to proceed through the remaining steps to obtain further required approvals. While a decision to proceed with the project is still to be taken, the Minister’s decision clearly puts the project over the threshold “go/no go” regulatory hurdle.

The decision also has broader significance in that it signals future oil and gas development projects that trigger federal reviews could be cleared, subject to stringent conditions dealing specifically with GHG emissions, including a requirement that a particular project achieve net zero emissions by a specified date.

From a broader regulatory perspective, the BdN Project review process illustrates that final decision-making authority with respect to projects invoking federal authority rests exclusively with the Minister (or the Governor in Council in certain circumstances).

This reality, in turn, raises a question of the extent to which the fundamental principles embedded in the Atlantic Accord — “joint management” and “equality of both governments in the management of the resource” — continue to apply.

Finally, the development advances the possibility that the BdN Project could become the first offshore production project in the world to trigger Article 82 of UNCLOS. In that event, further controversy is almost certain to arise around the question of who would ultimately bear the cost of meeting Canada’s obligation to make payments to the international community, based on production from the development.

* Energy Regulation Consultant, Co-Managing Editor Energy Regulation Quarterly.

- The Honourable Steven Guilbeault, “Decision Statement Issued under Section 54 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012” (6 April 2022), online (pdf): <iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/documents/p80154/143500E.pdf>.

- “As political divisions emerge over Bay du Nord, N.L. PCs lash out at federal Liberals”, CBC News (10 February 2022), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/bay-du-nord-divisions-politics-1.6346794>.

- See e.g. The Sierra Club Canada Foundation, “Media Statement on Reported Bay du Nord Approval” (6 April 2022), online: <www.sierraclub.ca/en/media/2022-04-06/media-statement-reported-bay-du-nord-approval>.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan: Canada’s Next Steps for Clean Air and a Strong Economy, Catalogue No En4-460/2022E-PDF (Gatineau: Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022); See also David V. Wright, “Canada’s 2030 Federal Emissions Reduction Plan: A Smorgasbord of Ambition, Action, Shortcomings, and Plans to Plan” (2022) 10:2 Energy Regulation Q 7.

- Darrell Roberts, “Federal government approves controversial Bay du Nord oil project”, CBC News (6 April 2022), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/bay-du-nord-approval-1.6410509>; The Premier also issued a formal statement see Executive Council Industry, Energy and Technology, News Release, “Premier Furey and Minister Parsons Comment on Bay du Nord Development Project” (6 April 2022), online: <www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2022/exec/0406n06/>.

- Darrell Roberts, “Oil industry calls Bay du Nord approval triumph, climate advocates condemn it”, CBC News (7 April 2022), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/bay-du-nord-reaction-1.6411013>.

- Paul Barnes, “CAPP Statement: Approval of the Environment Assessment of the Bat du Nord Offshore Development Project” (6 April 2022), online: <www.capp.ca/news-releases/capp-statement-approval-of-the-environmental-assessment-of-the-bay-du-nord-offshore-development-project/>.

- International Energy Agency, “Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector” (May 2021), online (pdf): <iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/0716bb9a-6138-4918-8023-cb24caa47794/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector.pdf>.

- See the further discussion below at note 35 of suggestions that the Minister had hinted that the BdN Project could be the last such project.

- SC 2012, c 19, s 52 [CEA Act, 2012].

- Government of Canada & Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, “The Atlantic Accord” (11 February 1985), online (pdf): <www.gov.nl.ca/dgsnl/files/printer-publications-aa-mou.pdf>.

- Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397 (entered into force 1 November 1994), online (pdf) <www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf>.

- Formerly Statoil, the Norwegian state oil company.

- The BdN Project is described on Equinor’s website see Equinor, “The Bay du Nord project” (last accessed 20 April 2022), online: <www.equinor.com/where-we-are/canada-bay-du-nord>.

- Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Atlantic Accord Implementation Act, SC 1987, c 3.

- Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Atlantic Accord Implementation Newfoundland and Labrador Act, RSNL 1992, C-2. These Acts are referred to together as the “Accord Acts”.

- Supra note 11.

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, Bay du Nord Development Project: Environmental Assessment Report, Catalogue No En106-243/2021E-PDF (Ottawa: Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, 2021), online (pdf): <iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/documents/p80154/143494E.pdf>.

- Ibid at 1.

- SC 2019, c 28, s. 1, known colloquially as Bill C-69.

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, supra note 18.

- Ibid at ii.

- Ibid at 145.

- Ibid.

- CEA Act, 2012, supra note 10, s 52(1).

- Ibid, s 53.

- Ibid, s 54.

- Supra note 20.

- Ibid, s 60(1).

- Ibid, s 64.

- Ibid, s 63(1).

- See e.g. ibid, s 60(1)(b).

- Supra note 11, Clause 1, emphasis added.

- Ibid, Clause 2(d), emphasis added.

- “Oil projects after Bay du Nord will be even harder to approve, says environment minister”, CBC News (20 April 2022), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/steven-guilbeault-bay-du-nord-1.6423671>.

- See e.g. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, “Advance 2030: A Plan for Growth in the Newfoundland and Labrador Oil and Gas Industry, 2018-19 Implementation Report” (19 February 2018), online (pdf): <www.gov.nl.ca/iet/files/advance30-pdf-advance-2030-2019-report.pdf>.

- Guilbeault, supra note 1.

- CEA Act, 2012, supra note 10, ss 5(1), 5(2).

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, News Release, “Government Accepts Agency’s Recommendation on Bay du Nord Development Project, Subject to the Strongest Environmental GHG Condition Ever” (6 April 2022), online: <iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/evaluations/document/143501?culture=en-CA>.

- Accord Acts, supra notes 15, 16.

- RSC 1985, c F-14.

- SC 2002, c 29.

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, supra note 39.

- Ibid.

- Supra note 12.

- Rowland J. Harrison, Q.C., “Offshore Oil Development in Uncharted Legal Waters: Will the Proposed Bay du Nord Project Precipitate Another Federal-Provincial Conflict?” (2018) 6:4 Energy Regulation Q 37.

- The word ‘to’ was used in early drafts of Article 82 and was intentionally changed to ‘through’. See International Seabed Authority, “Issues Associated with the Implementation of Article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Technical Study No: 4” (2009) at 20, online (pdf): <isa.org.jm/files/files/documents/tstudy4.pdf>; see also the discussion in International Seabed Authority, “Implementation of Article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Technical Study No. 12” (2013) at 27, online (pdf): <isa.org.jm/files/documents/EN/Pubs/TS12-web.pdf>.

- The main role of the International Seabed Authority under UNCLOS is with respect to the exploitation of seabed resources in the area beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, that is to say, the area beyond the outer limit of the continental shelf. See in particular UNCLOS, PART XI, Section 4. The Authority’s only responsibility with respect to Article 82 is to identify the recipients of payments or contributions that are made under Article 82 and to serve as the vehicle through which such payments or contributions are made. To date, no recipients of payments or contributions made under Article 82 have been identified.

- The potential payers are the federal government (upon which the legal obligation under UNCLOS rests), the provincial government (as the primary recipient under the Atlantic Accord of revenues from offshore developments) or industry (as the holder of the relevant production rights). See Patrick Butler, “Ottawa, N.L. disagree on who will foot hefty Bay du Nord royalty bill”, CBC News (21 April 2022), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/bay-du-nord-international-royalties-bill-disagreement-1.6424884>.